41. Strategy

The game of life is not so much in holding a good hand as playing a poor hand well.

H. T. Leslie (19c English composer)

Strategy is a general course of action (rather than a detailed plan). We often choose one out of habit, so it is common to be blind to some possibilities and recognise them only retrospectively. The purpose of this area is to reduce this occurrence. To do so, the basic ways of approaching problems are considered first and then a number of specific methods are suggested.

Facing the problem Problems

themselves are not a problem – we like them and create them when we don’t have them (e.g. crosswords, games etc.). The real problem arises when we don’t know how to solve them. But to be able to solve them, we need to face our problems first. Putting them off might bring temporary relief, but this often allows them to grow and makes things worse. However, it is usually not a good idea to deal with several problems at the same time, so when you decide to face your problems you need to prioritise. To choose which one to tackle first, take into account their importance and also which ones may grow if unattended.

What’s the problem?

Once you have made a choice, the first step is to clarify what the problem really is. This is often neglected, and it is more difficult than it sounds. Saying, for example, ‘I am not happy at work’ is not sufficient. You need to specify the cause of your discontent (e.g. ‘I am not paid enough’, ‘I am not getting along with my colleagues’, ‘my workload is too heavy’, etc.). If you think this is easy or that it doesn’t matter, try this example: John’s wife has left him, he is drinking too much, and is in danger of losing his job. What is his problem? (The prospect of losing his job? Drinking? Not coping well with the break-up? Something else?) Perhaps there isn’t a definitive answer, but there is no doubt that whatever you come up with will affect your choice of possible solutions.

Distancing: defining a problem accurately is essential because it determines what directions and solutions will be considered. This often requires looking at the problem from different perspectives, which is easier if you distance yourself temporarily from it. One way of doing this is to imagine, for example, that this is somebody else’s problem. Distancing does not imply neglecting your feelings, but attending to them separately, in order to be clearer about what the problem really is. Once you have defined your problem, you can choose a general strategy.

General strategies

There are four basic ways of dealing with a problem:

| I cannot (change the situation) | I can (change the situation) | |

| Not worthwhile (changing myself) | Isolation (e.g. ignore, close down) | Avoidance (e.g. leave) |

| Worthwhile (changing myself) | Adaptation (e.g. change your views) | Confrontation (e.g. new solutions) |

Let’s assume that your problem is, for example, working with colleagues who have radically different views (e.g. they are sexist). You can: ignore them (isolation), change the job (avoidance), adopt their views (adaptation), or try to address the issue (confrontation). Just to be clear, the term confrontation refers to confronting a problem in order to make some changes, rather than arguments or fights with others. Avoidance also doesn’t mean running away from a problem, but dealing with the problem by removing yourself from the situation. None of these methods is superior; it is always useful to consider all of them (sometimes they can even be combined, as in the case of a compromise). They are possible in almost any situation, although not all of them can always bring a desirable outcome. Which one is best in a particular situation depends on circumstances and the person(s) involved. What should be taken into account is the risk and possible consequences, what can be achieved and what can be lost.

Specific strategies

Choosing a general strategy may not always be enough. You also need to find a way to implement each step of the action. If you anticipate whatever may happen, play different scenarios in your mind, and find solutions for them, you should be on top of the situation. If you feel stuck, remember that there are always more possibilities than appear at first sight. Finding new solutions requires a new, fresh approach to the problem. Two main barriers to this are habit (choosing what you usually choose) and conformity (choosing what others usually choose). The following techniques may help you to overcome this.

Brainstorming: finding a solution consists of two mental processes: generating ideas and evaluating them. The trouble is that we usually carry these out at the same time. Brain-storming is useful because it separates them:

- Jot down in quick succession as many ideas as possible that come to mind in connection with the problem. Don’t evaluate them at this stage; sometimes the best solutions can be hidden in seemingly absurd thoughts.

- When this is done, pick one of these ideas and see what you can make out of it and how it can become practicable. Go through this process with the other ideas until you find a satisfactory solution.

Friendly advice: we always know how to solve somebody else’s problem better than our own! So simply ask yourself what advice you would give to somebody else in a similar situation.

Picture problem: do some doodling while you are thinking about your problem and when you finish, try to ‘read’ the drawing and see how it can help you solve the problem.

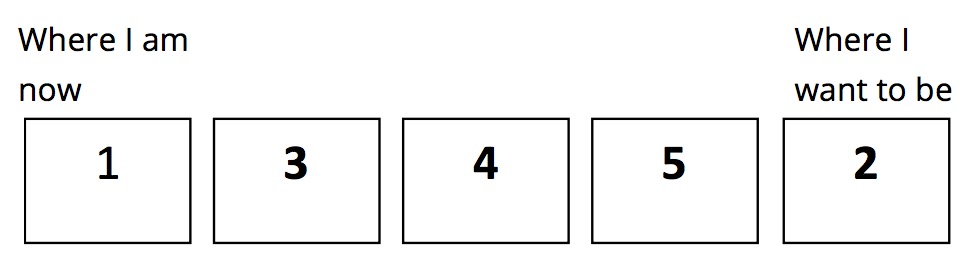

Story boarding: make a comic strip in the following order: start with the first square (where you are now), do the last one after that (where you want to be), and then fill in the ones in the middle, as shown in this simple diagram:

Emulating a solution: another way of coming up with new ideas is looking for a similar problem for which the solution is already known (for example, in the 19th century, aircraft innovators studied how birds and insects fly in order to figure out how to make machines that can do it). You can break it down into several steps:

- Who or what has already solved a similar problem?

- How?

- How can this solution help me with my problem?

Emulating a person: to get a different perspective on a problem, imagining what somebody else would do in the same situation may help you get unstuck. So suppose that a person you admire and respect (e.g. a fictional hero, spiritual guide, relative, friend, teacher) has the same problem and consider what he or she would do.

Incubation is a period of unconscious mental activity assumed to take place while you are not focusing directly on the problem. So, if a satisfactory solution cannot be found, it may help to distract yourself with some other light activity and allow intuition to take over (empirical support for the effectiveness of this approach can be found in Creswell at al article(1). Of course, this should not lead to procrastination or completely forgetting the problem.

(1) Creswell, J.D., Bursley, J., Satpute, A.B. (2013) ‘Neural Reactivation Links Unconscious Thought to Improved Decision Making’ in Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience, 8 (8), 863-869.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

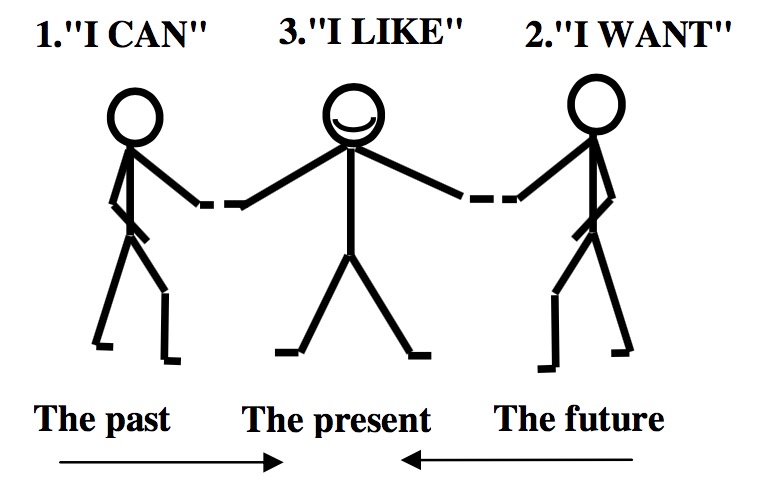

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.