The Map

Life experience is very complex and diverse. So, how can a model that may have a practical use be created?

Obviously, this complexity needs to be somehow simplified without losing its essential elements. One way of doing this is to locate common denominators of our experience, the underlying building blocks that life events are made of (for example, feelings, thinking, decision making, motivation, basic types of relationships etc.).

This has several advantages:

- First of all, there are a limited number of such basic areas (whereas there are an unlimited number of life situations and experiences that combine them), so it is manageable.

- We cannot deal successfully with complex issues if their underlying components are not addressed. Take, for example, smoking. Developing this habit depends on many factors such as our relationship to pleasure, self-discipline, susceptibility to influence, stability, gratification and so on. If there is just one weak link, it is unlikely that one can be in control of the habit.

- Finally, these basic areas enable endless combinations that can be applied in any situation, so everybody can use them in a way that fits his or her personality and circumstances.

Several criteria are used to locate these areas. They are all:

- Universal: they need to play a role in our lives regardless of culture, faith or gender, so that they are relevant to everybody.

- Irreducible: they cannot be reduced to each other. This helps with keeping their number manageable and avoiding overlaps.

- Transferable: the knowledge and skills associated with them can be applied in a wide range of situations.

These areas, of course, do not exist independently; they relate to each other. So, in addition, each of them must have its place within an overall structure – a map of the territory. The following explanation of how such a map can be created may seem in some places a bit complicated, but it is worth persisting. Understanding the map will enable you to be more creative in using it and to discover connections that are meaningful for you.

The dimensions of human life

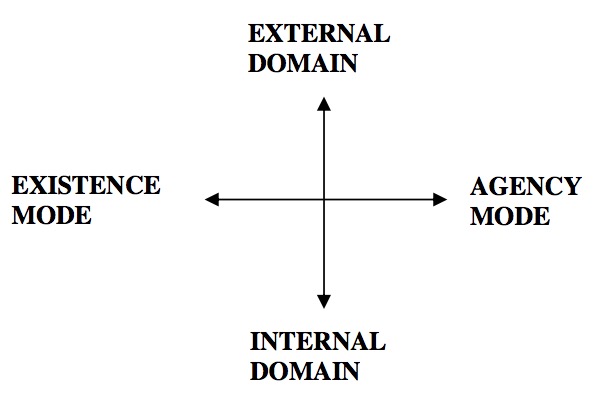

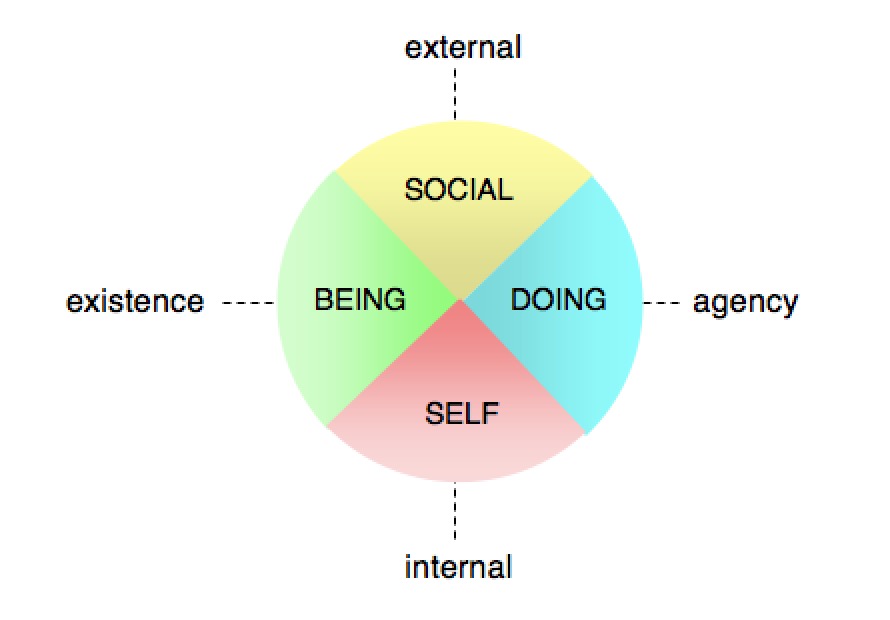

The design of the model starts with the fundamental dimensions of human life. They consist of two modes and two domains.

The two basic modes that define us as human beings are existence and agency: in other words, every person is (exists) and does (is able to make choices and act upon them – which is the meaning of the term agency). These two modes are applied in two general domains: internal and external.

The internal domain includes areas that focus on aspects of your inner world, such as thinking, feelings, desires, past experiences and so on, while the external domain includes areas directed towards the world outside and others (such as achieving, relating to others, communicating, etc.). Although, of course, these domains influence and mould each other, it is of great practical importance to make a distinction between them. For example, if you are afraid, you can respond to the situation that has caused the fear (say you are confronted by a tiger: you can run away, fight, freeze, etc.), or you can respond to the internal state, fear itself (you can suppress, accept, fight, project, or ignore it). The first type of responses would belong to the external domain, the second to the internal. These dimensions provide the coordinates for the map:

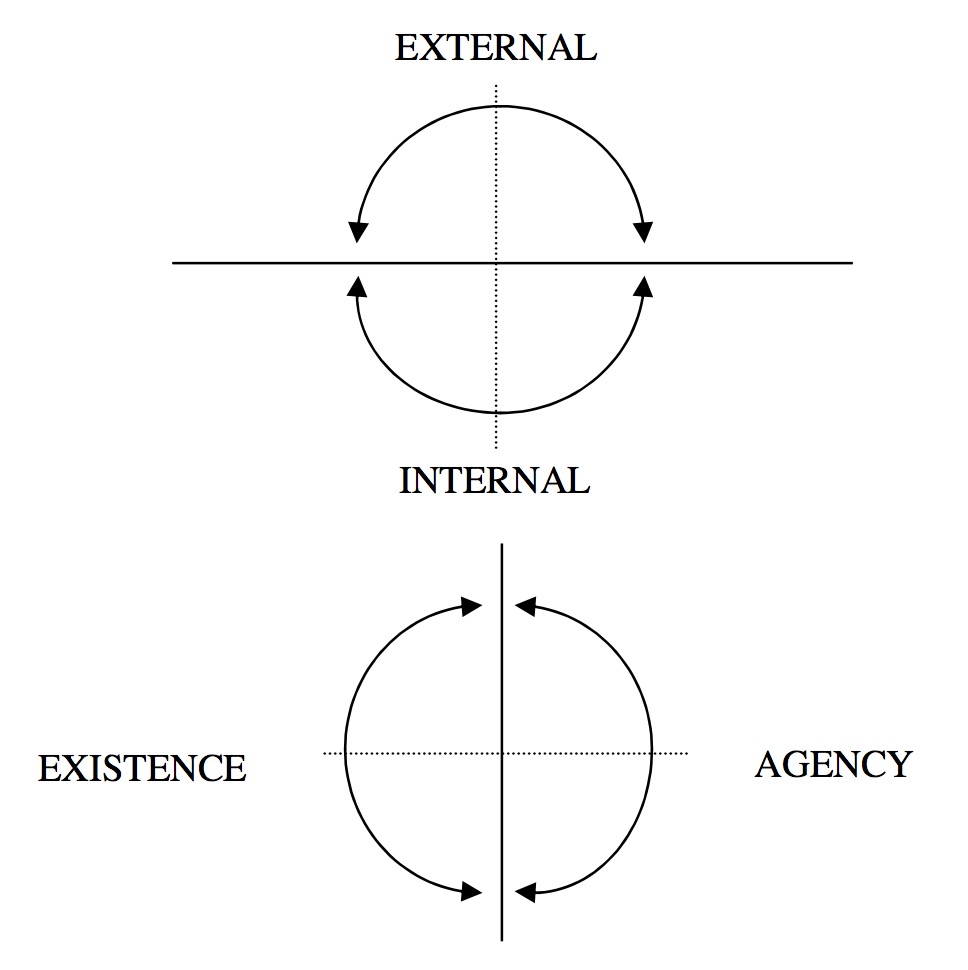

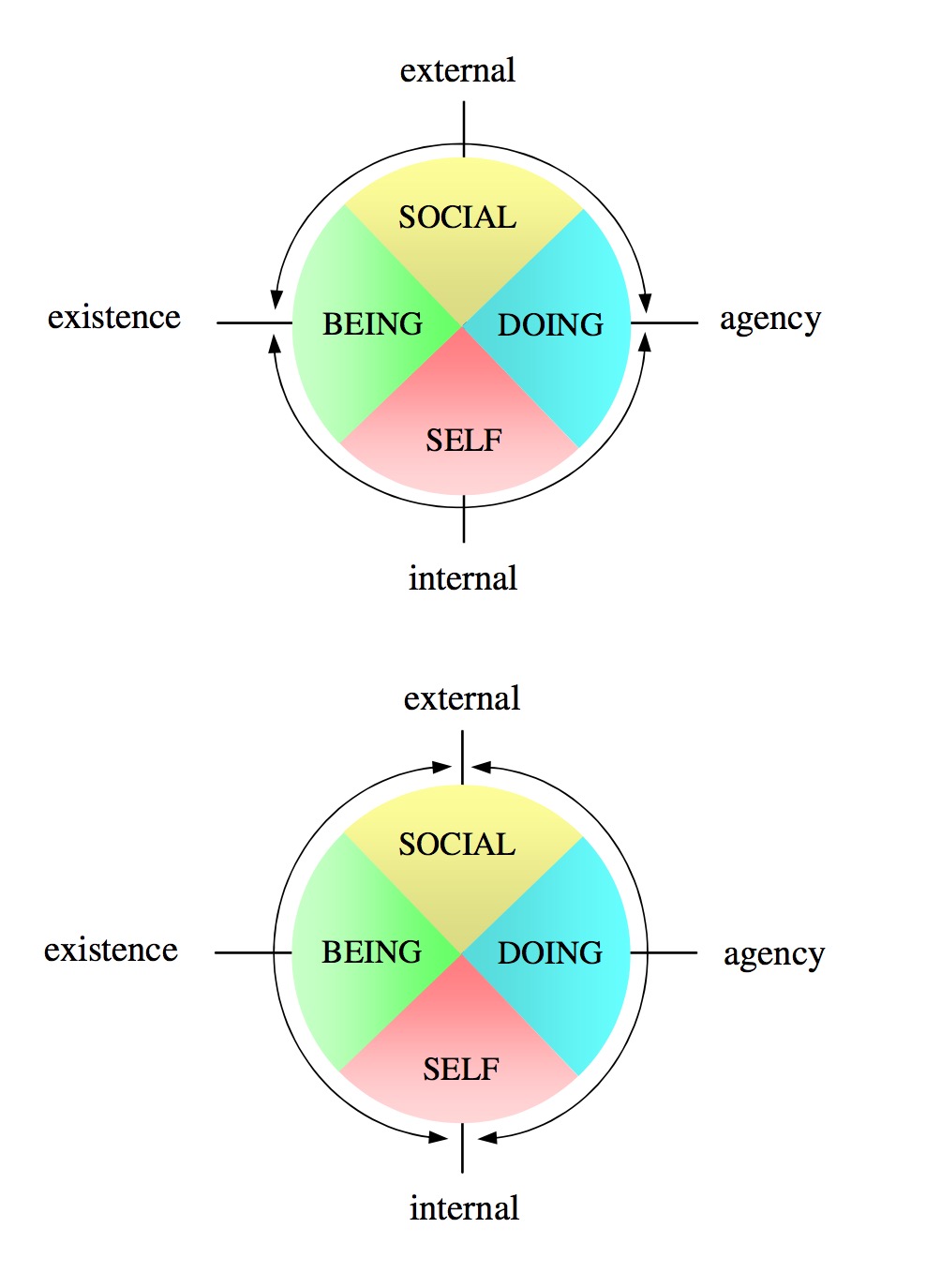

These diagrams show the ‘space’ that these dimensions cover:

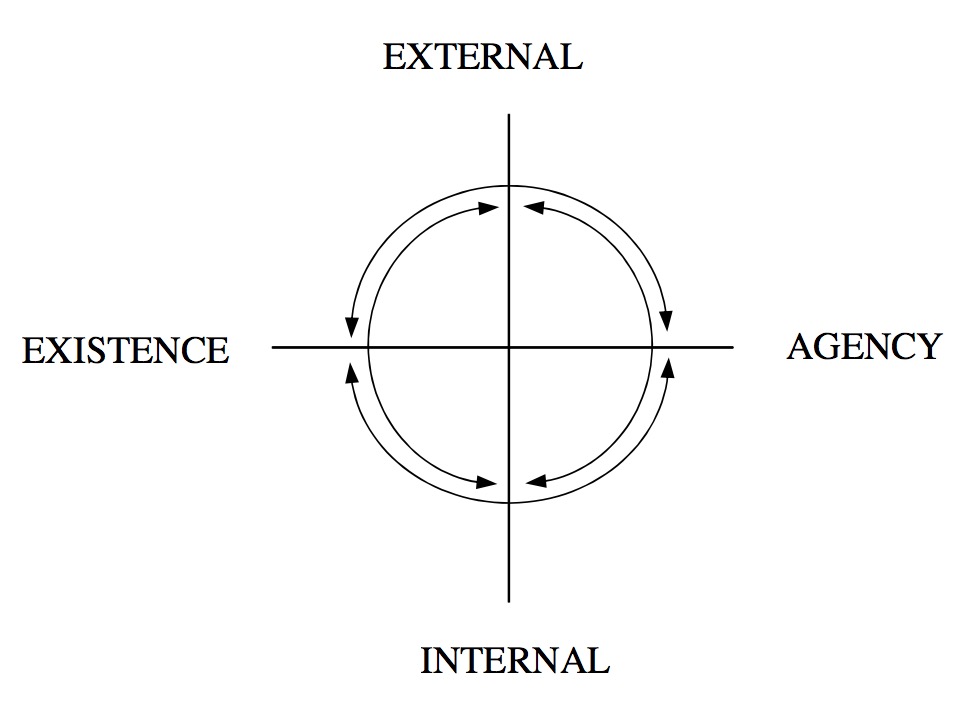

We can see that the modes and domains overlap. Put together, they can be presented in the following way:

Categories

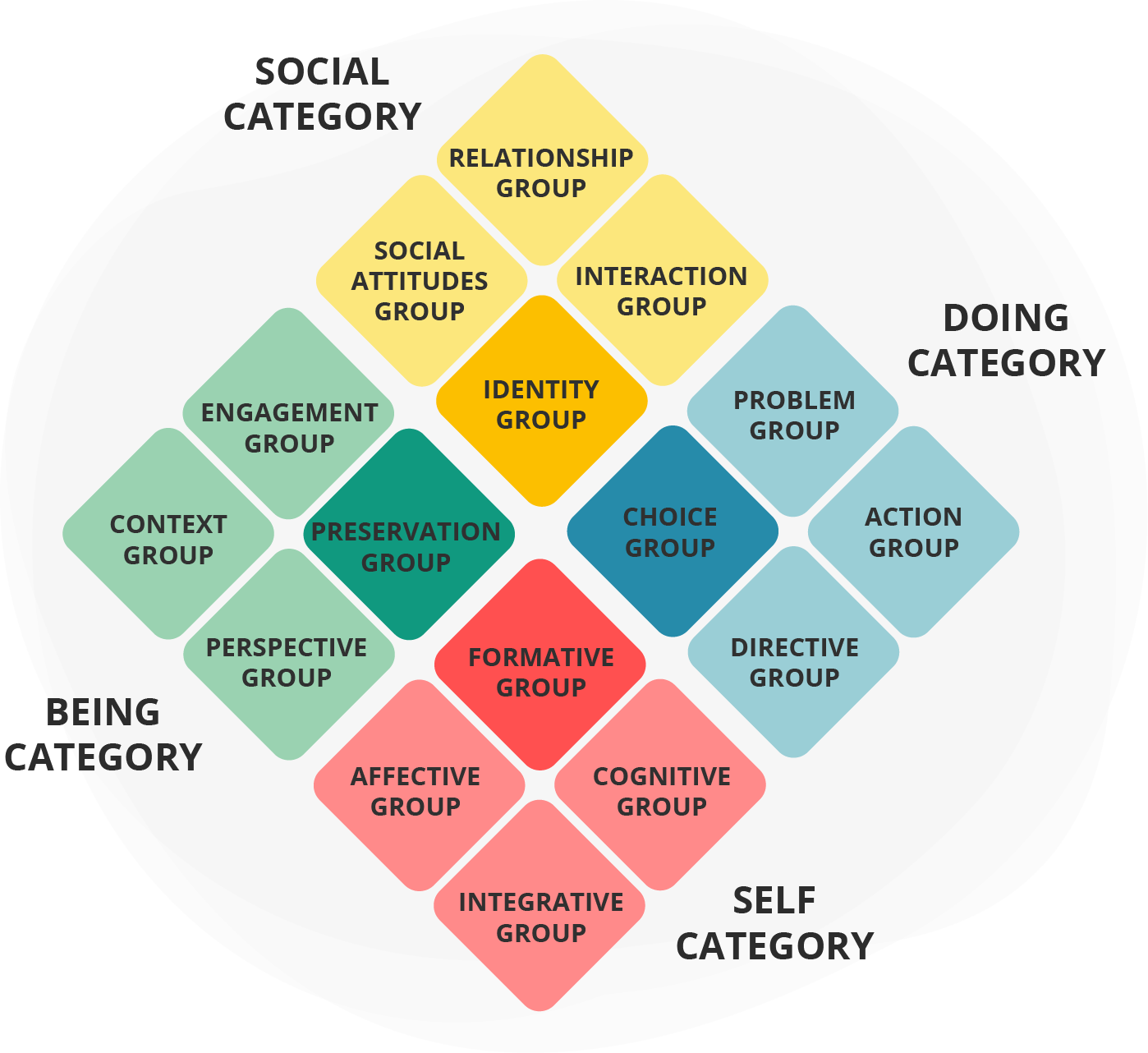

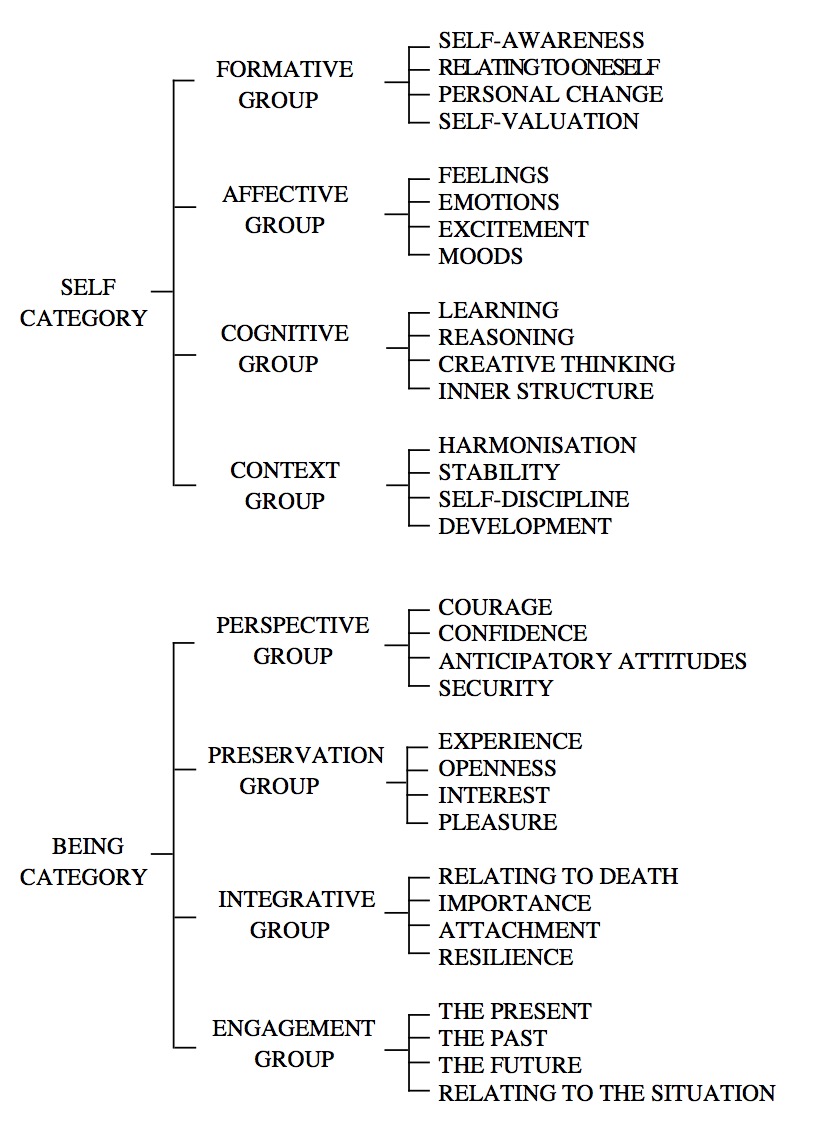

The areas mentioned above can be grouped around these coordinates to form four categories: Self category, Being category, Doing category, and Social category:

The Self category, at the bottom of the diagram, is the foundational or root category, because the other categories rely to some extent on it. This category includes areas that relate to ourselves (such as self-awareness, emotions, reasoning etc.).

The Being and Doing categories (at the sides of the diagram) complement each other. The Being category involves the ways we are in the world and the ways we perceive the world. The Doing category is concerned with what we do (our choices and actions). Being here means that the person is affected, while doing means that the person affects. So the Being category can include an activity if it is a re-action, and the Doing category can include inactivity if it is the result of one’s choice.

The Social category, at the top of the diagram, is mainly about interaction with others. It depends to some extent on the previous categories and also overarches them. Let’s see now how these categories relate to the modes and domains.

We need to remember that the modes and domains overlap. So, as the following diagrams show, the internal domain includes the Self category and one side of the Being and Doing categories; the external domain includes the Social category and the other side of the Being and Doing categories; the existence mode includes the Being category and one side of the Self and Social categories; and the agency mode includes the Doing category and the other side of the Self and Social categories. So for example, the Self category is entirely in the internal domain, but partly belongs to the existence mode and partly to the agency mode.

It is interesting that these categories seem to take positions that roughly correspond to the major areas of the brain (looking from left to right): our receptive abilities are mainly grouped in the anterior part of the cortex; the posterior part of the cortex is predominantly responsible for our agency; language, one of the central social aspects, is mainly situated in the left hemisphere, while the right hemisphere is believed to play a central role in the mental activities that are considered to be more subjective or personal (e.g. creativity, emotions); however, social emotions are, interestingly, closely associated with the left hemisphere. That the brain is organised in a similar way may be a coincidence, but it is good to know that there is a converging point in this respect, even if coming from a very different starting point. That said, we should be aware that these two systems are also very different, so there may not be any further similarities or parallels between the brain structure and this model.

Groups

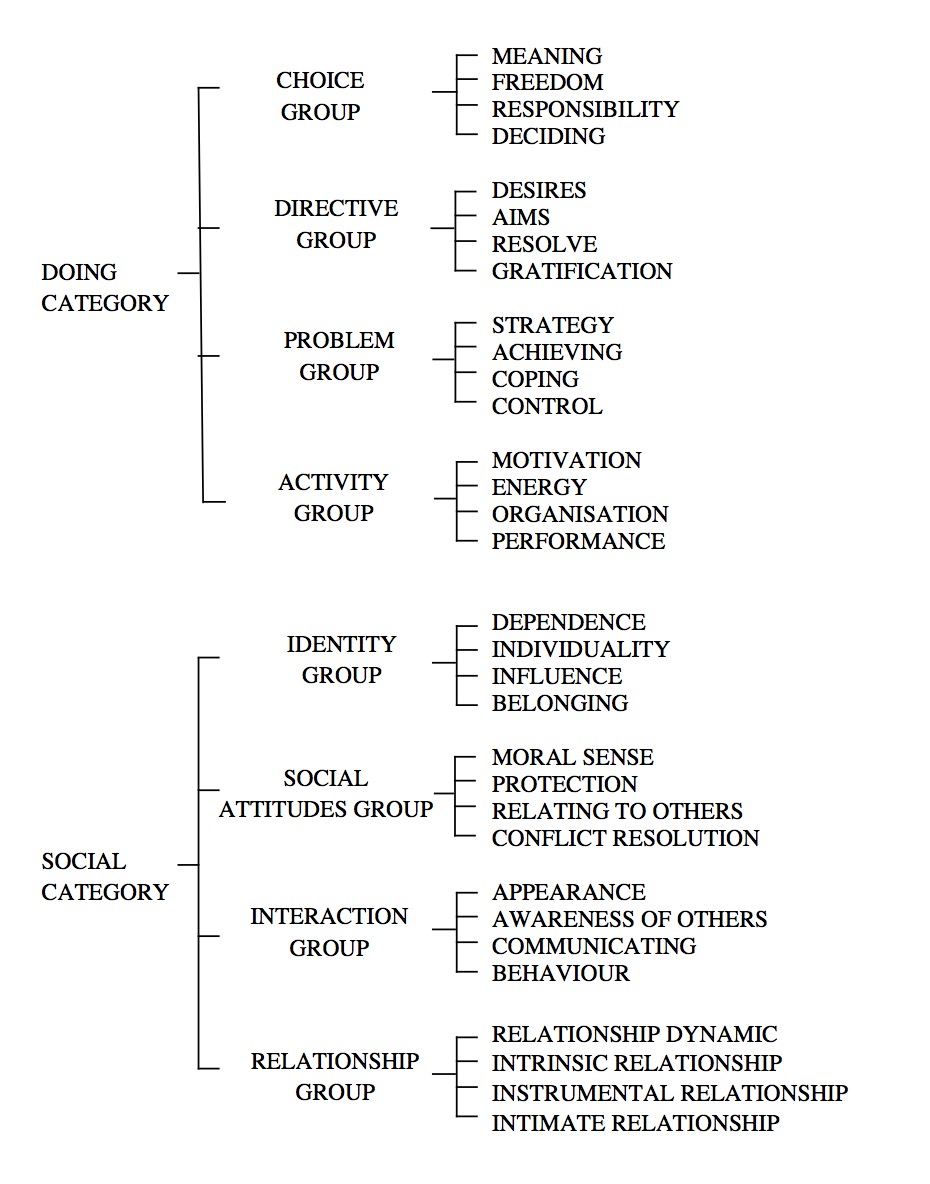

Each category consists of four groups, making sixteen groups:

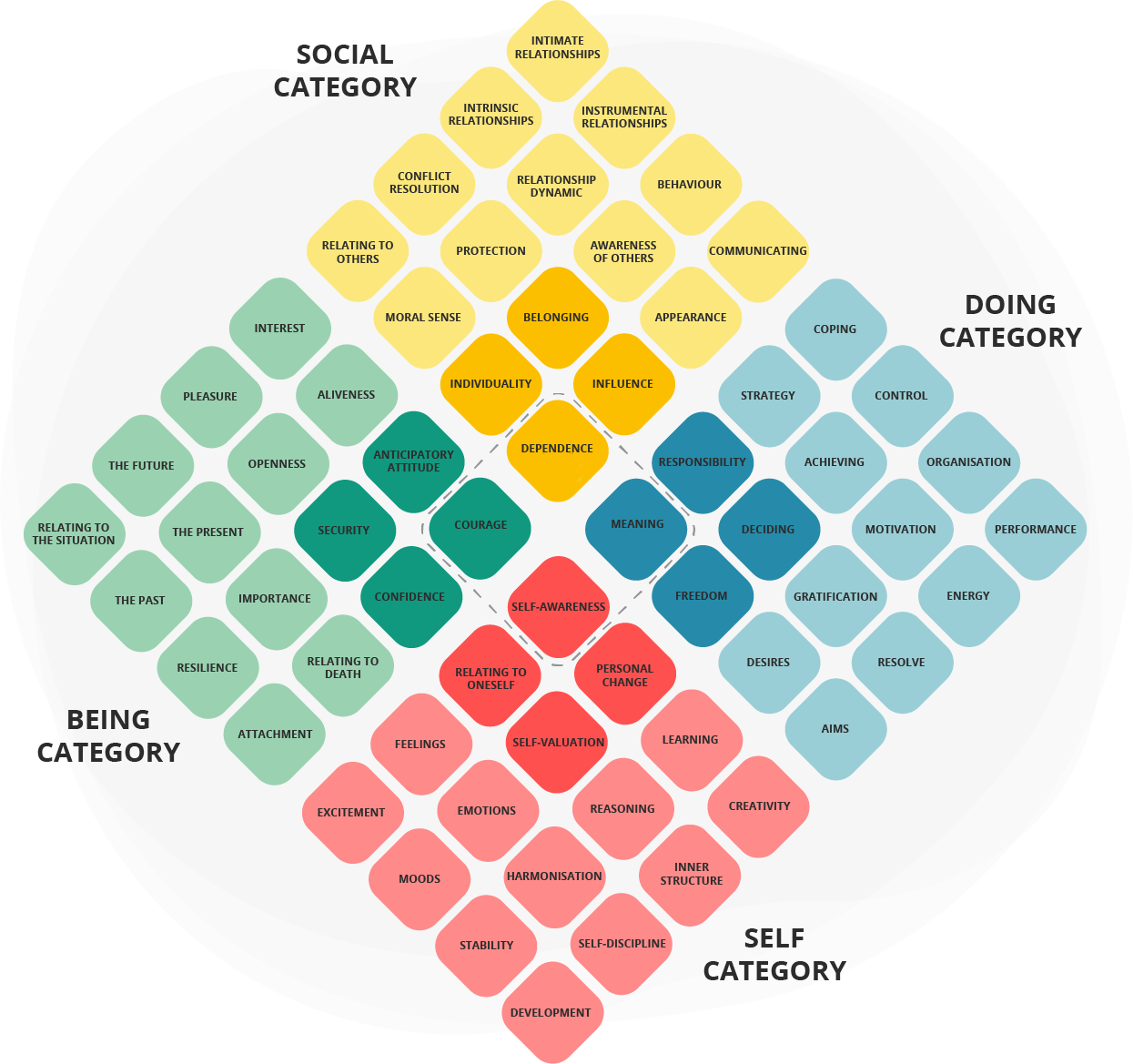

The groups relate to each other in the same way the categories relate to each other. The root group of each category is near the centre (e.g. the Choice group in the Doing category). There are also two side groups that belong to either different modes or different domains (the side groups in our example are the Directive group and the Problem group). The groups positioned at the corners are called top groups (the Action group in the Doing category). These have an overarching role but also rely on other groups in the category. Each of these groups consists of four areas, which make 64 areas in total. These are all presented in the final model:

Everything you experience and do involves a combination of some of these areas. They relate to each other within a group, as the groups relate to each other within a category and as the categories relate within the whole model. The root area of a group is the one nearest to the centre of the model. It usually directly affects the other areas in that group (Learning, Courage, Strategy, and Relationship dynamic are a few examples of root areas). Two side areas (relative to the root area) are usually counterparts, different poles of the central theme of the group (for example, Freedom and Responsibility or Creative thinking and Practical reasoning). The final area in a group (opposite to the root area) is called the top area. It is usually based on and overarches the other areas in the group (Self-valuation, Resilience, Control and Intimate relationship, are some of these).

The position of each area in the model is mainly determined by the modes and domains they belong to (see The Dimensions of Human Life, above). For example, the area Relating to oneself belongs to the internal domain and the existence mode, while Personal change (from the same group) belongs to the same domain, but the agency mode. Protection in the Social category belongs to the external domain and existence mode, while Desires in the Active category belongs to the internal domain and agency mode. A more detailed description of each group and area is provided in the rest of the materials, which should clarify further their positions. It should be pointed out at this point though that even if each area has its unique position and function, this is not to say that their characteristics are sharply divided. Indeed, the seed of an opposite domain or mode seems to be present in almost every area or group (in a sort of yin-yang fashion). So, the positioning of the areas is based on these tendencies using the principles of fuzzy logic rather than on binary, black-and-white thinking.

You may have noticed that some areas are positioned on the axes of the map. These areas have properties of either both modes or both domains. For example, in the Personal category Self- awareness, Self-valuation, Harmonisation and Development are positioned on the internal axis and encompass both the existence and agency modes. Let’s have a look at why this is the case:

- Self-awareness: we are inevitably aware of ourselves to some extent, but to interpret and understand the processes within our mind, we need to be pro-actively reflective. Therefore, both the existence mode and the agency mode play a role in this area.

- Self-valuation (which includes self-respect and self-esteem) relates to both our existence and our agency.

- Harmonisation, which is mainly concerned with resolution of inner conflicts, is first of all about harmonising or balancing two basic modes, existence and agency, in their various forms (security and freedom, feelings and intellect, being and doing etc.).

Development involves natural processes (e.g. going through puberty) as well as conscious directing and willingness to put some effort into it, which requires one’s agency.

The Rings

The map also consists of two rings: the inner and outer (separated by a dotted line and darker shades of colour in the diagram). The four groups in the inner ring are those positioned around the centre of the map, while the areas that comprise the outer ring are those on the periphery of the map. The areas in the inner ring predominantly relate to the concept of one’s own personality, while the outer ring is predominantly concerned with the interaction with a larger framework within which we are situated – our reality, or world-concept. The number of groups in the inner ring is smaller, but they underlie the ones in the outer ring (better conceived as inner and outer sides of the same ring). Each of these, as mentioned, is also the root group for their respective categories. What’s the difference between the personality-concept and the Self category? While the Self category consists of constitutive areas of ourselves, our personality is relationally co- constructed, so all four categories are involved (e.g. the area belonging to the Social category plays an important part in forming and defining our identity).

Using the map

As the compass, this map too includes four cardinal directions that provide orientation in this field. The equal size of each category (i.e., the same number of areas in each) reflects their parity in terms of importance and value. The map may look suspiciously orderly – human life seems much more messy and irregular. It is conceivable, though, that behind the seeming disorderliness, there is a certain order on a basic level. In a similar vein, the complexity and variety of the whole biological world is based on 64 combinations of gene sequences (which is, coincidentally, also the number of areas in this model). True, genes are more tangible, but as the psychologist Shotter points out, ‘just because, in dealing with entities such as “intentions”, “beliefs”, and “motives”, we are dealing with quality without substance, it does not mean to say that great orderliness is not possible’(1). In any case, this model is not an attempt to describe reality, but a map created for a practical purpose. And, like any other map, this one is necessarily a simplification of what it represents. It can still be a useful tool in several ways:

- It provides an overall view and indicates the relationships and dynamics between the areas. This can be very important (e.g. in balancing being and doing in your life).

- It may help in locating the root of one’s problem, by going back towards the centre of the model. Say you lack energy (even though you are physically ok). You may, of course, look first at the area Energy. However, if this doesn’t help, you can move to the root area of that group, which is Motivation, and further down the line consider the areas Decisions and Meaning (on which your motivation may depend).

- Another way of utilising the map is by paying attention to the other areas in the same group. In the above example, perhaps balance is what is needed, so it may be worthwhile considering the area Organisation (which deals with planning and use of time) that is the counterpart to Energy.

- The map can also be used in a creative way – play with it, let intuition take over and see where you end up.

The areas in linear order

A two-dimensional map can be helpful, but if we want to approach personal development systematically, it is necessary to organise the areas in successive order (one after another). Let’s see how this is achieved from the map. The first category in the model to be addressed is the Personal category. This is because the areas that belong to this category, such as Self-awareness, Reasoning, Emotions, or Self-discipline, are the basis for the rest of the model. The Being category comes before the Doing category because it involves the ways we perceive the world, which is normally prior to agency and deliberate action. The Social category comes last because it is the most complex, and also because it relies to some extent on the other categories.

The first group within each category is the root group (in the centre of the model). In regard to the side groups, a group that belongs to the internal domain precedes a group that belongs to the external domain, and a group that belongs to the existence mode precedes a group that belongs to the agency mode. The last groups to be addressed in each category are the top groups (placed in the corners of the model).

The first area approached within each group is the root or foundational area of that group (always the one nearest to the centre of the map). It is followed by the side areas. As above, if they belong to different modes or domains, the one belonging to the internal domain precedes the one belonging to the external domain, and the one belonging to the existence mode precedes the one that belongs to the agency mode. This leaves the order within the eight pairs of side areas that are part of the same mode or domain undetermined. Which area comes first within these pairs is based on common sense (e.g. Awareness of others, which includes listening and empathy, seems naturally to precede Communicating). The last area to be presented within a group is the top area (positioned opposite to the root area).

This order does not imply that one area is more important than any other. It only indicates that some of them should be approached prior to the others from the same group or category.

This list contains all the categories, groups and areas, presented in a linear form.

(1) Shotter, J. (1982) ‘Contemporary Psychological Theory – Human Being: Becoming Human’ in Dufour, B. New Movements in the Social Sciences and Humanities. London: Maurice Temple Smith, p.88.

(1) Shotter, J. (1982) ‘Contemporary Psychological Theory – Human Being: Becoming Human’ in Dufour, B. New Movements in the Social Sciences and Humanities. London: Maurice Temple Smith, p.88.