19. Anticipatory Attitudes

When I look back on all these worries I remember the story of the old man who said on his deathbed that he had had a lot of trouble in his life, most of which never happened.

Winston Churchill (20c British statesman)

This area covers mental dispositions towards events that are not experienced but anticipated. These attitudes can affect our mental state, performance and even our health. We will consider here three such attitudes: worrying (characterised by apprehension), as well as optimism, and pessimism (characterised by overall positive and negative attitudes respectively).

Worrying

Worrying can be defined as an apprehensive reaction to the possibility of an undesirable outcome. It has characteristics of anxiety (because uncertainty is involved) and fear (because it has an object). The object of worry is always at a space or time distance, so relief from worry through immediate action is not possible, which is why it can be very frustrating.

Is worrying really useful?

The emotional impact of worrying may help focus the mind on the problem. Goleman (of Emotional Intelligence fame) writes that ‘worry is, in a sense, a rehearsal of what might go wrong and how to deal with it; the task of worrying is to come up with positive solutions for life’s perils by anticipating dangers before they arise.’(1) However, not only are worries unpleasant, but they usually become circular and repetitive, occupying our mind to the extent that they, in fact, prevent us from finding a solution: ‘worriers typically simply ruminate on the danger itself, immersing themselves in a low-key way in the dread associated with it while staying in the same rut of thought.’ This, in turn, makes assessing the situation more difficult and can be exhausting – much time and energy can be wasted on worrying. Just think about the last time you worried a lot: did it really help?

So, why do we worry?

Despite being unpleasant and mostly useless, there are many secondary reasons why worrying is so common:

- It is sometimes used as a means to: get attention (e.g. children notice that adults who worry get attention, so they start worrying too); maintain a sense of self-importance (e.g. a manager may worry excessively as it makes him feel important); sustain connection with everyday life (e.g. grandma’s worrying about her grandchildren may be a way of feeling connected to them); protect one from facing deeper fears or pains (e.g. a fear of loneliness may be covered by worrying that one’s partner may have an affair).

- Worrying is also closely related to a desire to maintain control, so it can be motivated by the belief that mental suffering will somehow affect the outcome: ‘the worry psychologically gets the credit for preventing the danger it obsesses about.’ This superstition is reinforced simply because most events that one worries about never happen anyway.

- The other common reason why we worry is to prove that we care (e.g. ‘If I don’t worry about my kids, this means that I don’t care for them’). However, these two are not the same, which is easy to see if you compare ‘I don’t care” with ‘I don’t worry’. Clearly you can care without worrying.

None of the above is very helpful long term. In fact, worrying is useful only if it initiates a solution-focused action, otherwise it is pointless. So go and do something about what makes you worry if you can (e.g. if you worry about an exam, start revising). If nothing can be done, there is no point in ruining the present by worrying about the future or something that is happening elsewhere. If what you worry about doesn’t materialise, worrying is unnecessary; if it does, all the more reason to enjoy the present while you can. Admittedly easier said than done, but the good news is that, unlike fear, worrying is learned (usually in childhood) through copying others. So, worrying is a habit that, as with other habits, can be modified and even unlearned.

How to reduce worrying

Just saying ‘stop worrying’ does not help; in fact, it can even increase worrying. However there are a number of other things you can do to reduce worrying.

Worry less

- Think about the worst thing that might happen and make decisions about what to do in that eventuality. If you are prepared for the worst, whatever happens you have nothing to worry about!

- It is easy to exaggerate how likely an event is to happen, so consider what the chances really are that what you worry about will actually happen.

- Distractions such as doing something engaging or socialising can also help (although worrying may come back later).

- Write your worry on a small piece of paper, make a ball of the papers and throw it into a bin.

- Use your imagination (e.g. imagine attach your worry to a balloon and ‘watch’ it flowing away, put your worry in a box, bury it, drop it into a lake, etc).

The above may help with transient worries, but some of us worry all the time about anything and everything. This intervention can be very effective if you worry habitually:

Worrying adjourned: allocate a limited period (e.g. a half hour, say between 7.00 and 7.30pm) for worrying. If you start worrying at any other time, just say to yourself ‘I will worry about it later.’ When the time comes, go on but don’t force yourself to worry, you may realise that actually there is nothing to worry about!

Let’s now consider two other ways of anticipating outcomes.

Optimism and pessimism

Broadly speaking, optimism is a general propensity to see things in a positive light, while pessimism is a tendency to focus more on the negative aspects of a situation. There are advantages and disadvantages to both. A superstition that you are destined to fail, a feeling of futility and bad luck that pessimism can lead to may sabotage your efforts and motivation to get anywhere. Optimism, on the other hand, can bring enthusiasm, increased energy and motivation. It is not surprising that people who have positive attitudes tend to be more productive, less stressed, and more confident about the future.

However, if such attitudes become blind optimism or fantasy, it can result in unrealistic expectations or carelessness that can be harmful in the long run. There are some advantages to being pessimistic. For example, it can prevent naivety that usually leads to underestimating risks and ultimately disappointment. Pessimism can motivate you to work harder and can prepare you better if things don’t turn out well. Surely, then realism must be best? Realism is important because it can moderate both, but it does not provide the emotional energy that pessimism and optimism do (anxiety and enthusiasm, respectively). So what then?

The synthesis

Both optimism and pessimism can be good and bad:

- Bad pessimism just believes in bad luck;

- Bad optimism just believes in good luck;

- Good pessimism is being aware of what is or can go wrong;

- Good optimism is believing that if something goes wrong, you will be able to deal with it.

In balance, the synthesis of realistic pessimism and realistic optimism may be the best choice. This is not the middle-ground, but getting rid of unhelpful elements of both and combining helpful ones: don’t expect either good or bad luck. Instead, be aware and prepare for what can realistically go wrong and then let yourself be reasonably optimistic. In other words, be pessimistic in your mind, but optimistic in your heart.

(1) Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional Intelligence. London: Bloomsbury, p.65.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

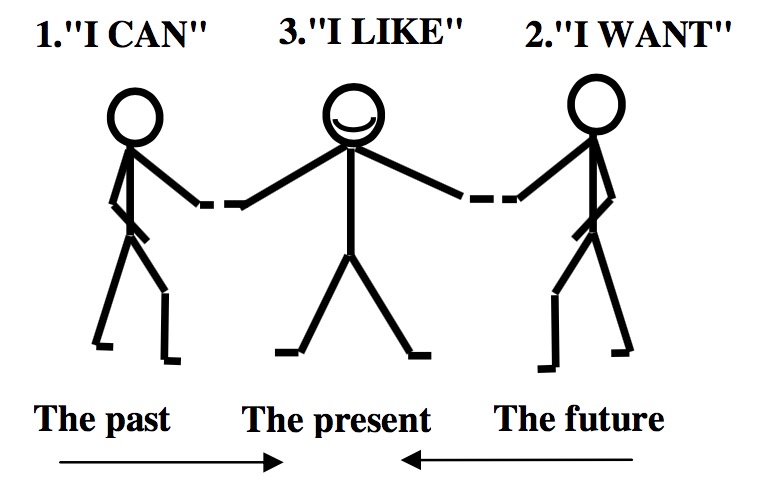

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.