12. Inner Structure

Man is what he believes.

Anton Chekhov (Russian 19c writer)

Our beliefs, concepts, thoughts and ideas play an important role in the way we perceive reality. However, our beliefs do not exist independently; they tend to be organised in meaningful and sensible ways. This net of mental concepts creates our belief system – or inner structure. We all, practically from birth, start building (and re-building) this system and continue doing so throughout our lives, so it is the result of an interaction between ourselves and the world. Some elements stem from adopting common knowledge (science, religion, cultural beliefs), and some are the result of unique personal experiences (e.g. believing that people are/are not generally trustworthy). However, we need to be aware that although these mental structures correspond to reality to some extent, they should not be identified with it. In other words, we should not assume that our beliefs are the indisputable truth. If this happens, the mental structure that they create is taken for granted and left unattended, with the consequence that it cannot accommodate new experiences and could even fall apart.

The purpose of our inner structure

The main purpose of our inner structure (or belief system) is to integrate, i.e. make a meaningful whole of various experiences, and enable our mind to expand. Fragmented, conflicting, or too rigid beliefs can lead to prolonged anxiety, poor adaptability and a number of other personal and interpersonal problems. Yet, psychologists have observed that people find invalidation of their basic beliefs highly threatening and have a vested interest in maintaining them even when they are maladaptive, for fear of disorganisation.’(1) So let’s see first how we can make changes to our belief system in a controlled way in order to allow for its better integration as well as its development. After that, two exercises that can facilitate its integration and development (Mind- mapping and Laddering) will be described in some detail.

Integration

The following characteristics lead to good integration:

- Congruence: your beliefs and ideas should not conflict with accepted facts or your experience (e.g. a belief in racial superiority lacks congruence as it conflicts with the known facts).

- Consistency: your beliefs should not contradict each other (e.g. rejecting a notion of free will and yet accepting a legal system based on personal responsibility may be inconsistent).

- Completeness: your belief system should account for all the facts and experiences. This means that nothing should be left out (e.g. a claim that only competition drives evolution may be incomplete – cooperation plays a role too).

- Cohesiveness: all the elements of your inner structure should be connected and superfluous ones excluded. You don’t need to believe in something if it is not necessary (e.g. extraterrestrials are not necessary in order to explain crop circles).

Developing inner structure

Integration is not enough – we sometimes need to develop our beliefs. It is difficult and often deleterious to try to maintain this structure unchanged (Don Quixote and King Lear are famous and tragic literary examples of trying to do so). Adapting your structure to reality rather the other way around reduces conflicts and contributes to personal growth. The following characteristics can help us develop our inner structure:

- Flexibility: being able to modify and adapt your ideas to incorporate new experiences or information instead of dismissing or misinterpreting them to fit the ideas that you already have. Take this example: you believe in homeopathy and come across some research concluding that homeopathy is ineffective. Would you dismiss it? Now imagine that the article actually claims that homeopathy is effective. Would you be equally dismissive?

- Open-mindedness: willingness to consider alternative interpretations. Open-minded people are not without convictions – they are just not overly attached to every part of their belief system and are prepared to examine arguments that differ.

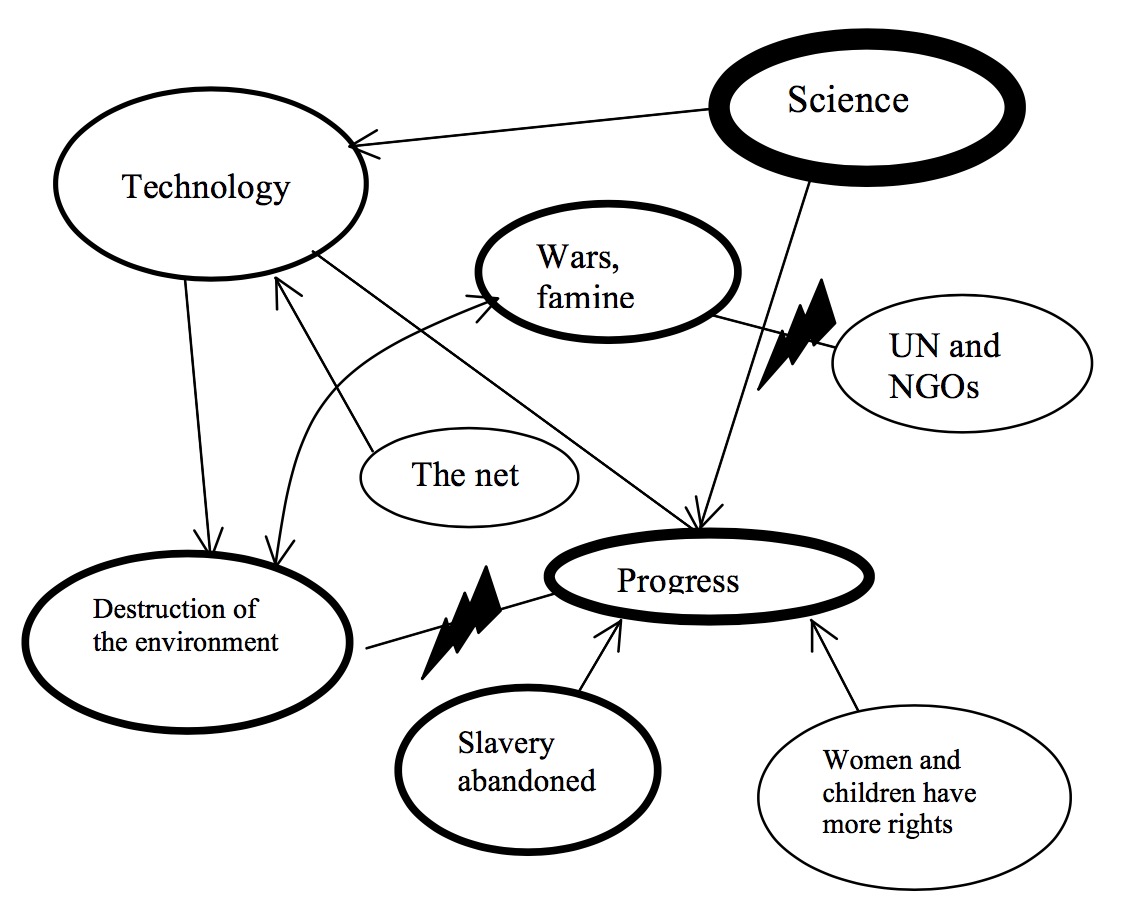

Mind mapping can help you clarify relationships between various ideas or parts of your inner structure and reveal possible contradictions. Place the main topic (or a pivotal belief) in the centre of a clean sheet of paper and circle it. Then, place related ideas in smaller circles and make connections between them that are meaningful to you. You can use different colours or lines to make it all clearer.

This is an example of the mind-map:

Central beliefs (that may not be the most prominent ones) are near the centre – in this case the belief is in human progress.

Laddering

Our reactions are often the result of our beliefs that we take for granted. Below our thoughts on the ‘surface’ there are always deeper, more general assumptions of which we may not be fully conscious. This exercise can help us become aware of these buried beliefs and examine whether or not they are really justified.

You can start from any situation, perhaps something you think or have said. Simply ask yourself a ‘why do I think this’ question. Whatever the answer is, ask the same question again until your deep assumptions or beliefs are revealed. Bear in mind two things when doing this:

- To avoid going in the wrong direction, always ask ‘why do I think…?’ rather than just ‘why?’ For example, if you ask, ‘why do I think my friend is disrespectful?’ an answer may be ‘because she is late’; if you just ask ‘why is she disrespectful?’ an answer can be because of her upbringing or genes – very different. In the first case, you explore your beliefs, in the second you look for an outside cause.

- ‘Why’ questions should always move from specific to more general. Let’s continue with the above example:

– Why do I think that being late is disrespectful? (Note that this question is not only about the friend anymore, it is more general).

– Because it means that the person doesn’t care.

– Why do I think so?

– Not sure… Perhaps it is not always the case…At this point you can stop asking questions and examine to what extent this assumption is really valid.

When you get to the point of recognising that your deep beliefs may be challenged it is not unusual to experience some discomfort and resistance. If so, don’t give up – this is exactly when this exercise can be really fruitful.

(1) Epstein, S. (1993) ‘Emotion and Self-Theory’ in Lewis, M and Havilland J. (eds) Handbook of Emotions New York; London: Guilford Press, p.322