26. Openness

Individuals who are open to experience are able to listen to themselves and to others and to experience what is happening without feeling threatened.

Brian Thorne (a person-centred therapist)

Openness is often associated with either open-mindedness or frankness. These meanings are addressed in the areas Inner structure and Intrinsic relationships respectively. Here, the term signifies permeability between oneself and the world. Therefore, this is not only about cognitive openness or talking openly to others, but openness to our experiences in general. Being able to regulate openness can significantly affect our quality of life, so this will be the main focus of this area.

What openness is

It may sometimes feel as if we have ‘holes’ or ‘cracks’ in our personality. These are usually the result of unresolved personal conflicts or unhealed wounds and they make it difficult to become a harmonious whole. They often cause oversensitivity and tension, which in turn lead to putting barriers between oneself and the world. Openness is different. It refers to the permeability of the person as a whole that facilitates exchanges with the environment. Openness enables us to transform sensations into personal experiences – in other words, to internalise the external world. This is how we make an experience our own.

Why it is important to regulate openness

Some experiences can increase our energy while some can drain it away, so being able to regulate to which ones and to what extent you open up may be important. This is not straightforward though. If we are not careful, certain situations can make us open up or close down when we don’t want to or more than we want to. Also we may develop the habit of being too open or too closed, and respond to situations inadequately in this respect. We will see soon what we can do to be more in charge of this ability, but we ought to consider first why, when and to what extent to open up.

Why to open up

The main reason why it is good to open up is that it enriches life (the quality of your experience) – without it, even an eventful or abundant life may feel unfulfilling. Being overly closed allows little exchange, which is associated with feelings of boredom and emptiness. Openness also has further benefits:

- It enables you to recognise new possibilities – if you are not open, you are likely to miss some opportunities.

- It contributes to learning and personal development.

- It can enhance creativity.(1)

- Being closed most of the time can create an inner pressure, which may lead to acting inadequately (e.g. being too quick or too slow to engage with the situation).

- Being closed may also make others feel excluded and may affect the quality of relationships.

When and to what extent to open up?

No answer to this question can be generalised as it depends on situation, your personality and the context. Let’s consider, for example, to what extent and why you should be open to difficult, sad or painful situations (e.g. homelessness, wars or famine in remote countries, ecological disasters). Obviously, ignoring them makes you less informed and less able to make good judgements. Furthermore, openness in this respect can motivate you to do something.

On the other hand, openness can make you feel despondent if you cannot do anything, ‘It is none of my business’ or ‘nothing I can do about that’ are most common justifications for not being open to difficult issues. Even if you don’t think in that way, you may sometimes be energy depleted or too emotionally vulnerable to face them. So, you need to make a choice from one situation to another if and to what extent you will open up, taking into account how strong you are and whether or not you can do anything. Bear in mind that we usually can do something more often than it seems at first glance (e.g. we can at least bring an issue to the attention of others) so it is always worthwhile thinking about it or asking around before concluding that we are powerless.

How to open up and close down

Nice experiences and positive emotions open us up spontaneously and reversely, harsh experiences and negative emotions tend to close us down. These things are difficult to invoke at will though, so let us see what else we can do in both cases.

Opening up

- Avoid making assumptions and judgements in advance (e.g. ‘this event/person is going to be boring’).

- Have positive expectations – expect that you will find something valuable in your experience.

- Use your imagination (imagine, for example, opening the curtains or the window in front of your forehead).

- Relax – physical and mental tension makes us rigid and more difficult to open up.

- Exercise your natural curiosity – get interested, reach out.

- Look around, rather than just in front of you.

- Try to reduce the chatter in your mind (do you really need to think about your report while playing with your kids?). This chatter is the greatest barrier to fuller experience.

This and the following exercises should increase your ability to regulate a degree of openness.

Opening up: with the help of the above suggestions, open up and allow the situation to gradually draw you out. Don’t force anything, just absorb any sensations that you are experiencing in a relaxed state and without making any judgements. You can practise this in various situations but leave those in which you have to interact with others for later, when you complete all the exercises.

If you find it difficult to open up, it would be worth examining why this is the case. It may be simply a habit, but it may have a deeper cause, such as past fears. Consider that even if they were justified then, they may be blocking you now unnecessarily.

Closing down

Sometimes we can be opened too much, which can make us feel exposed, vulnerable, overwhelmed and even hurt. This especially applies to highly sensitive persons, but learning how to close down at will can be useful to everybody, as we all find ourselves occasionally in situations that can be overwhelming (e.g. very busy or crowded places). Here are a few suggestions:

- Lower your expectations and prepare mentally, as a disappointment or unpleasant surprise can open you up when you don’t want or more than you want.

- Shut down mentally: if you find it hard to do so, try to imagine pulling the shatters down in front of you.

- Create mental armour: imagine a shield or armour that encloses and protects you. It doesn’t matter if it is real or not, it can still have an effect (as an imagined spider can).

- Ignore whatever is going on around you – if you find it hard to do so, focus on a distant object (e.g. a cloud or tree outside).

- Use tunnel vision: just focus on what is in front of you. This is what, for example, many commuters do spontaneously in crowded stations, in order to avoid sensory overload.

- Find something to think about to keep yourself in your head (e.g. calculate your taxes or make a shopping list).

Closing down: experiment with the above suggestions till you find a combination that suits you best. Any situation (e.g. waiting for a train) can be used for this purpose.

Both – and

This last exercise is a combination of the above two and it will not only improve your control, but will also crystallise the difference between these states.

Openness control: open and close a few times in the same situation and monitor the effects. Start first with situations that do not involve others and when you feel more in control of this ability, try it in social situations.

(1) Rogers, C. (1954) ‘Toward a Theory of Creativity’ in Parnes, S. J. and Harding, H. F. (eds) A Source Book for Creative Thinking. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1962, p.67.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

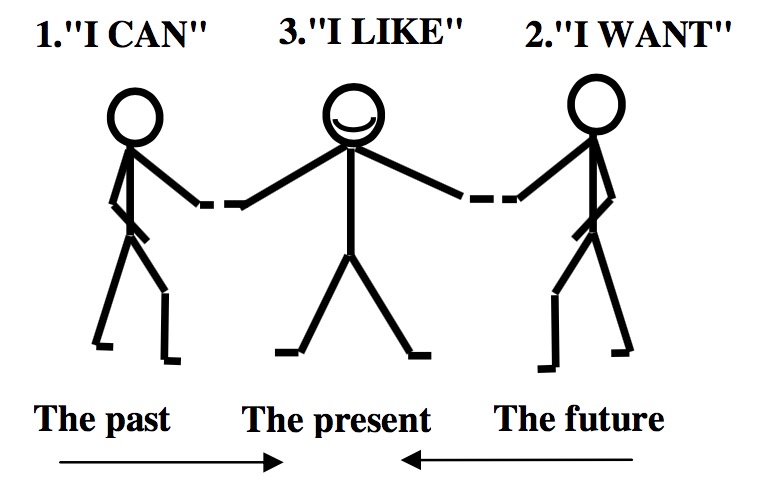

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.