48. Performance

Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish painter)

Beside the tangible benefits that competent performance can bring (e.g. recognition. financial rewards) it also enhances self-esteem and a sense of achievement. Moreover, psychologists claim that ‘human beings have an innate need to be competent, effective and self-determining’(1) – in other words, doing well feels good. So, we will focus here on what contributes to competent performance.

Precursors to competence

These steps can prepare you to perform competently:

- Practice: competence depends more on how effectively we utilise our abilities (whatever they are) than what abilities we have. Research supports the notion that talent plays a smaller role in an achievement than effort and time put into an activity(2). So, saying ‘I am not good at it’ is just an excuse. The more you practise, the better you will get.

- Doing everything well: trying always to do well regardless of what you are doing and its importance will help you perform competently when under pressure because it becomes a habit.

- Importance: giving too little importance to what you do can make you overly laid back, while giving too much importance can increase anxiety to the point of being paralysing. So try to find your own ‘Goldilocks zone’ in regard to this and keep importance within that range – this simply means taking what you are doing seriously but not too seriously.

- Being your own judge: if your priority is to satisfy your own standards rather than those of others, their praise or criticism can still have a positive effect on your performance but the negative effect will be reduced.

- A good physical and mental shape: if you don’t feel well or are tired or worrying about something, you will hardly be able to concentrate and perform well.

What makes competent performance

These are some characteristics of competent performance (this list may not be exhaustive, and not all of them are always necessary):

- Efficiency means doing things at the right time, in the right place, with as little waste of energy as possible.

- Practicality means keeping in mind the aim before and during an action. It can be a safeguard from spreading yourself too thinly or getting bogged down with details. This may not apply though if the process is more important than the final result.

- Carefulness is achieved by keeping attention on what you are doing rather than thinking about something else.

- Elegance makes a performance look spontaneous, natural and easy. It is attained through persistent and attentive practice.

- Improvisation implies flexibility in thinking, actively seeking new ways of accomplishing a task. This may be important if something unpredictable happens. However, complicating matters needlessly is not improvisation but a waste of time. The easiest or simplest way is often the best. There is usually a good reason why something is done in a particular way.

- Creativity is an ability to produce something new, and it can make any work more pleasurable. Creative ideas arise more easily in the process, rather than from prior thinking.

- Effectiveness means completing what you have started. Incomplete tasks can leave you open and continue to affect you. Not everything can be accomplished though – sometimes a project has to be abandoned. That also means finishing, as long as it is a conscious decision, rather than just leaving an unfinished work behind to linger.

The final performance: to do your best some authors recommend imagining that what you are doing is the last thing you will do in your life. This can indeed improve the quality of a performance because it focuses the mind on the present. However, caution is called for, because such an attitude may lead to forgetting the wider context.

Optimal performance

Competent performance or doing well, in most cases, does not mean striving for a maximum but an optimum. This means doing your best within reasonable time, and taking into account the circumstances (e.g. other commitments). What’s wrong with perfectionism? Well, our lives are limited and we all have competing demands on us. Trying to do something perfectly often means doing badly or completely neglecting something else, as we get short of time or exhausted. In fact, perfection is often unnecessary; consider, for example, this principle:

The 80/20 principle (or the Pareto rule) suggests that roughly 20% of your efforts usually brings 80% of your results (the other 80% of your effort brings only 20% of results). For instance, 80% of floor is done in 20% of vacuum-cleaning time. Perhaps this does not apply in all cases and perhaps those 20% are worth 80% effort, but even with this caveat, bearing this principle in mind can be useful for optimising your time and effort. Can you think of a situation or activity to which this principle can be applied?

Measured performance: sometimes we underperform not because we put too little energy in our activity but because we push too hard. Force can be sometimes justified (e.g. breaking into a house in flames to save the occupants), but this is different from being forceful. The latter implies applying too much pressure (on objects, yourself or others) which can make things go wrong. For example, enthusiasm about a particular project can be highly beneficial, but being overly enthusiastic can lead to burn-out, being careless, and it can be annoying and put others off. Measured performance, on the other hand, means accomplishing what you intend with an optimal effort. It implies being considerate, going on with your task without causing discomfort and with minimal pressure on anything and anybody. While being determined means not giving in to yourself or others, being measured means not mistreating yourself and others and treating even objects (e.g. the tools you are using) with due respect.

Flow and the larger perspective

Flow (studied and popularised by the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi) means being fully immersed in an activity. It is characterised by an intense and focused concentration to the point that you forget yourself as well as time and, in a sense, merge with what you are doing. Flow is normally a highly enjoyable and effective state of mind – as its activities (your brain-waves if you like) are in sync. Some would even claim that the state of flow, sometimes also referred to as ‘the zone’, is necessary for great performance. As it benefits both you and your performance, nurturing this state really pays off (as many sportspeople know). To get in flow, choose a challenge that matches your skills; then, forget everything else, focus fully on your activity, and enjoy the ride! Flow is not always great though.

Sometime we need to be aware of other things in order to avoid, for example, tripping over or breaking something – or missing an appointment. Some people may be able to be in flow and keep other things at the back of their minds, but this is difficult and requires a lot of practice. If you are not there yet and are concerned that you may be carried away with an activity, decide in advance how far you will go or for how long and remember to remember (set an alarm if necessary!). Try also to develop a habit of looking around when you have a mini-break or when you spontaneously come out of flow (when you complete something, for instance).

Performance control is similar to awareness control exercise (p.154) but in action: d) Choose an activity, such as washing dishes. Try to fully focus on your performance, get into flow. If your mind wanders off, bring the focus gently back to the activity. e) Expand your awareness and become aware of other things while you are still doing what you are doing. f) Trytoalternatebetweenthesetwostates.Withsome practice, you will be able to contract and expand your awareness at will.

(1) Spence, J. T. and Helmreich, R. L. (1983) ‘AchievementRelated Motives and Behaviours’ in Spence, J (ed.) Achievement and Achievement Motives. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, p.24.

(2) Kaufman, S. (2014) ‘Practice Alone Doesn’t Make It Perfect’ in Scientific American (online): https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautifulminds/practice-alone-does-not-make-perfect-studies-find/

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

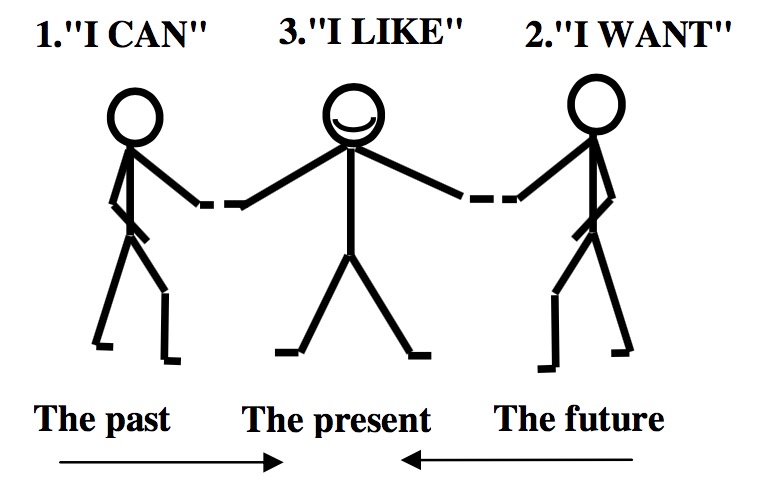

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.