55. Relating to Others

Remember, no one can make you feel inferior without your consent.

Eleanor Roosevelt (American politician and activist)

In this area we will consider respect and acceptance, as well as comparing ourselves with others, which is implicated in symmetrical and asymmetrical ways of relating to others.

Respect

Respect simply means treating people as subjects, not objects. This implies respecting their existence as well as their agency (freedom to make choices). We sometimes treat people as objects in order to fulfil our desires or gain a sense of control. This, however, leads to disconnectedness that induces a sense of isolation, even when with others. As already discussed in relation to self-respect, respect doesn’t need to be earned as it is derived from our intrinsic value of being human. So, there is no excuse to treat anybody disrespectfully (even prisoners are supposed to be treated with some respect). Besides, we are more likely to be treated with respect if we treat others with respect.

Acceptance

Acceptance and tolerance are sometimes used interchangeably, but they are not the same. Tolerance implies putting up with others, suggesting that they are an inconvenience to be endured. True acceptance is more than that: it primarily means accepting that people can be different. It also involves an attempt to understand others, rather than honing in on their perceived faults. Even if they have some shortcomings you don’t have to be troubled by them. This is not to say that we should put up with everything. Bringing up what bothers you is easier though if the other is first accepted as a person; in fact, accepting others as they are and trying to understand their motives can be the first step in eliciting a positive change. In addition, acceptance can be enriching as it involves opening up to something different, and it makes being accepted more likely (while rejection, of course, has the opposite effect).

Why accepting others may not always be easy

There are a number of reasons for this:

- Insecurity: differences make some people apprehensive and insecure. This has roots in our ancestral past, but nowadays our fear of difference is usually unjustified: in fact, a difference can be enriching and the familiar may be a bigger threat (some conmen specialise in taking advantage of their compatriots abroad who would rather trust them than ‘foreigners’).

- Projections: we may be sensitive to some aspects of others because it is too close to home. In other words, an inner conflict is projected outside (e.g. you don’t accept somebody’s sexual orientation because you are struggling with your own).

- Generalising: making individual assessments requires effort, time and intelligence, so we easily end up generalising: we reject a whole community or group on the basis of limited experience with one or a few individuals; or we prejudge individuals on the basis of their nationality, culture, religion, or the way they dress, talk or look. This undermines personal differences and is often misleading and unfair.

On the way to acceptance: choose an individual (or a group) that you find difficult to accept. Try first to find out why (e.g. he doesn’t smell nice) and then imagine that this thing (the unpleasant smell) is gone. Can you now accept that person? If you still can’t, perhaps it is you – not accepting somebody for no reason cannot be justified. Do you feel threatened? Do you project something onto the other(s)? Are you generalising? Once you are able to accept the person, you can turn to the offending thing itself (the smell): why does it concern you? Can he do anything about it? Can you do anything about it (e.g. talk to him, change your view, understand)? Understanding makes acceptance easier, so don’t assume, ask and explore (e.g. somebody may smell bad because of a health condition rather than negligence).

Comparing

We often compare ourselves with others but this overlooks the fact that people (as other objects) actually cannot be compared; it is only possible to compare their characteristics. So, saying ‘he is better’, or ‘she is superior’ is a misnomer. Such statements are just groundless generalisations. Comparing one or a few characteristics and then generalising from them is simple, but it doesn’t do justice to the complexity of human beings and human life. One can play or look better or have more money, but it does not mean that she is a better or superior person (e.g. one who plays better may not cook better). Not even all characteristics can be compared, but only those that can be measured using the same yardstick.

So, if you compare some aspects of yourself to others bear in mind that nobody is a better or worse person and that everybody is, in fact, a unique and essentially incomparable individual. Personal (a)symmetry That we are not comparable as people is the basis of personal symmetry or equality. It does not mean that we are all the same or equally good in everything.

Equality allows for differences; it only implies that personal asymmetry, manifesting as inferiority and superiority, is inadequate. They may be goaded by circumstances or others, but where you stand in this respect ultimately depends on you and your way of thinking. There are some states of mind, such as envy, that breed feelings of inferiority and superiority. Envy is usually the result of distorted perception, when one aspect of somebody’s life (e.g. their wealth) is extracted from the whole. Nobody has everything though; it is likely that the one who envies has something the envied one would desire (privacy, free time, fewer responsibilities).

Similarly, those looked down on are likely to have something to offer if one is open enough to recognise it. In fact, looking down on others is often a compensation for lacking genuine self-respect. It is used to raise one’s self-esteem and feed one’s ego in order to feel good about oneself and is quite common. Inferiority and superiority are actually two sides of the same coin. If you believe that somebody is below you, you must believe that somebody is above you too (and the other way around). Neither are conducive to healthy and fulfilling relationships. Take this example: some people take an inferior position in response to a favour; however, this is more likely to make those who have done them the favour feel uncomfortable rather than pleased. On the other hand, when people give up on superiority and inferiority, relationships become more open, relaxed and spontaneous.

Challenging asymmetries: imagine being with somebody you know. Notice whether your position seems higher or lower than the position of that other person. If it does, this may indicate feelings of superiority or inferiority, respectively.70 Consider why you have these feelings. If you find that they are linked to something specific, imagine situations in which this factor is irrelevant (e.g. one’s status or wealth on a desert island, or one’s looks in a war zone) and try to make your positions more equal. Superiority and inferiority may also arise because inter- dependence, needs or importance are not reciprocal. If so, consider how these could be balanced better.

Functional asymmetry

Functional asymmetry (asymmetrical functions that we may have) is sometimes important, even necessary, but it does not give anyone license for abuse, degradation or humiliation. Parents and teachers, for example, usually have superior knowledge, experience and skills to children, but this does not make them superior people. The way to avoid inferiority in a subordinate position is to accept functional asymmetry, without giving up on personal symmetry! Respecting the qualities of others and freely accepting limited subordination in order to learn or perform a task do not create inferiority. For example, you will learn to drive better if you can accept the superiority of your instructor’s skills, but this does not require accepting an unequal relationship.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

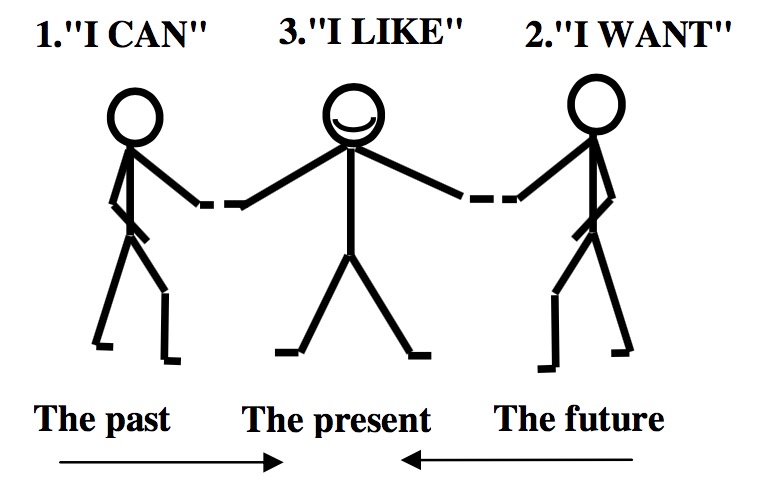

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.