34. Personal Freedom

Life is like a game of cards. The hand that is dealt you represents determinism; the way you play it is free will.

Jawaharlal Nehru (Indian statesman)

When we talk about freedom we usually have in mind physical or political freedom (e.g. freedom of movement or freedom of speech). Personal freedom or autonomy is different – it is psychological freedom from drives and restraints within us. We can never be completely free from them (nor it would be desirable), but we can turn these determinants into influences over which we have a degree of freedom. Let’s see how to do it.

Why personal freedom matters

Personal freedom is freedom of your mind from what determines your thoughts, feelings and behaviour. It is based on our ability to exercise choice. Although some circumstances may be more favourable for acting autonomously, choice is always possible regardless of circumstances. Lazarus, a renowned psychologist, asserts that ‘a person chooses rather than the environment, and sometimes this choice operates against the usual environmental pressures.’(1) Even people in the prison or the concentration camp have a choice (e.g. to despair or hope, to co-operate with their captors or not). But why does it matter? Wouldn’t we be more carefree without it? Wouldn’t our lives be easier if somebody or something else (e.g. a super-computer) told us what to choose and do (e.g. which socks to put on, what to eat, what programme to watch on TV, who to date, etc.)? Perhaps, but this is what makes us human – without personal freedom we wouldn’t be much different from machines; so the value of autonomy is not just instrumental but intrinsic. Think about how you feel when somebody is telling you what to do. She may have good intentions and her advice may be sound; yet you may feel almost irrational resistance – this is because you are trying to protect your autonomy. It is worth remembering though that what limits your personal freedom can be inside rather than outside you.

How do I know if I am free or not?

Some of your thoughts, feelings, behaviour, values or attitudes may indeed be pre-determined. A usual sign of this is that you always act in some situations in the same way for no good reason or even against your better judgement. For example, you inevitably get defensive and snap when you feel criticised. If you suspect that this may be the case, ask yourself ‘do I have to act (think, feel) in this way, or I am free to do otherwise?’ If you believe you are free – test it next time, prove it to yourself. If you feel that you don’t have a choice and it bothers you, you may want to do something about your inner determinants.

Determinants

Determinants are strong drives that compel us to act, think or feel in a certain way, even if this is not necessarily best for us or what we really want. They can be grouped in several categories:

Physical determinants: everybody is, to some extent, determined by inherited predispositions (usually called nature). It is useful, though, to think about them as potentials (for good and for bad). These potentials can be fully realised, inhibited or directed. Imagine somebody who has exceptional genes for playing the violin. With practice, she may become a great musician, but if she grows up in a culture that does not use the violin or if her family discourages her from playing, she will never become a great violin player despite her genes. The same can be applied to other potentials. Even if we accept a dubious claim that the propensity for aggression might be in our genes, it will not develop if we don’t exercise it. Such a propensity can also be directed constructively into competitive sports (e.g. rugby or boxing) or some vocations (the military) rather than being wasted on street fights. Controlling physical determinants is achieved through Self- discipline. Self-discipline not only enhances our choices, but also enables us to act upon them, put that freedom in practice. Your genes matter, of course, but you do not have to be a slave to them, do not let your genes push you around!

Social determinants (or nurture) consist of internalised directives laid out by significant others in childhood. They can be very strong and their effects can be long lasting. Some may be useful and provide a sense of security and social orientation, but we do not need to slavishly follow them. Reflective thinking (figuring things out for yourself) leads to greater autonomy in this respect. This is not to say that you have to necessarily make a change; you can maintain the same values or attitudes and still be autonomous as long as it is the result of your reflective choice.

Personal determinants: we ourselves can limit our freedom by sticking to certain habits or responses. Such determinants can relate to the past, present or future:

- We can be conditioned by our previous experiences. If you had an accident while learning to ride a bicycle, you may become predisposed against cycling (or even sport in general) throughout your life.

- The conditioning can be the result of a self-image that you want to create or maintain in the present. For example, you may start smoking or vaping to look cool (to others or to yourself) and then make a habit of it.

- We can also be conditioned by our own expectations, what we want to become. For example, you may be ridiculed for crying and vow never to be a ‘wimp’ again. Years later, you may find yourself incapable of crying, although the original situation and the promise are long forgotten.

As in previous cases, these determinates are not always bad and can make life easier. However, it is important to recognise what they are, in order to avoid being enslaved by them.

Transcendent determinants are forces beyond us that are supposed to shape our lives, such as destiny, karma, the stars, or the ‘laws’ of evolution (e.g. some believe that evolution dictates men to be polygamous and women to be monogamous). Not everybody believes in them though. If you do, it may be worthwhile considering how they affect your personal freedom.

Dealing with determinants

It sometimes may be difficult to establish which of the above determinants are at play (they may also be compound). So here is a generic exercise that can help you with reducing their effects even if you are not sure to which category they belong:

De-conditioning: if you recognise that your reaction is pre-determined, follow these steps:

- Examine its roots first: what does that situation remind you of? How far back can you trace the same pattern? Where is it coming from? Such feelings, thoughts or behaviour may have been motivated by some payoffs; are these still valid?

- Consider other possibilities: what choices do you have? What else can you do? How would you really like to respond in such situations?

- Now, imagine reacting differently and observe how you feel. If you experience discomfort or anxiety consider if these feelings are justified. If they are not, repeat the same till they are gone.

- Try what you imagined in real situations and see how it goes. How do you feel about it? Are there any benefits of being free to react differently?

Even if you decide that your old pattern is better, you will at least know and feel that you have a choice.

Inner democracy: so what do we do when we free ourselves from the tight grip of these determinants? They will still be there, but we can establish inner democracy: let everything in your mind (your thoughts, emotions, desires, values, concerns, dreams) to have a voice but let nothing take over. In other words, acknowledge every aspect of yourself, but allow none to rule you. Not being attached to your mental states and processes (see, for example, Disidentification exercise) helps not only establish but also maintain this inner democracy.

(1) Lazarus, R. (1975) ‘The Self-Regulation of Emotion’ in Levi, L. (ed.) Emotions: Their Parameters and Measurement. New York: Raven Press, p.62.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

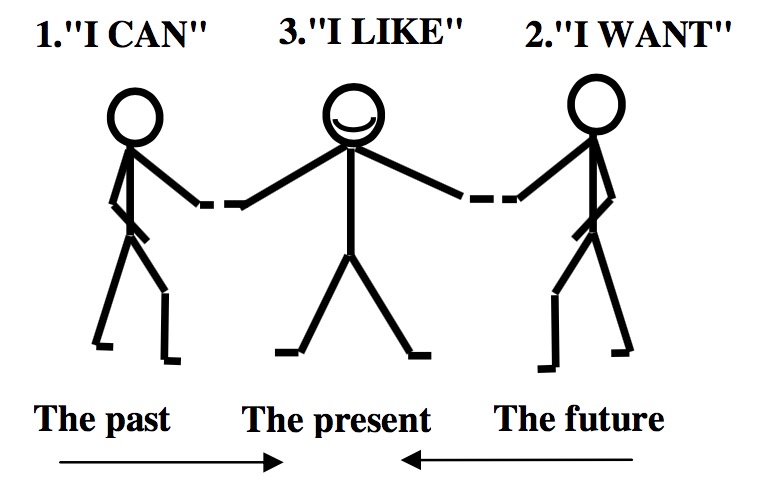

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.