45. Motivation

Every man without passions has within him no principle of action, nor motive to act.

Claude Adrien Helvetius (18c French philosopher)

Motivation is an inner push to act. Psychologists suggest that it ‘is an innate human drive and begins in infants as an undifferentiated need for competence and self-determination’.(1) There is no doubt that being able to affect our motivation is of great value, as little can be done without it. We are all too familiar with the debilitating effect that a lack of motivation can have. Learning about it is important not only to motivate ourselves, but also to be able to motivate others. This area will consider various types of motivation and how it can be increased.

Negative and positive motivation

- Negative motivation (an aspiration to preserve the existing state and avoid whatever threatens to make it worse) is associated with negative feelings (e.g. fear).

- Positive motivation (moving further, expanding, improving the existing state) is associated with positive feelings.

The former can sometimes be stronger, but the latter is more effective in the long run. Besides, negative motivation often ends in experiencing a lack of energy and desire for rest – not from the trigger, but from the unpleasant feelings that one is motivated by. It is interesting though that whether motivation is positive or negative often depends on our perspective (e.g. you can run from an attacker, or you can run for safety). To transform negative motivation into positive, you need to focus on what can be gained, rather than on what has been or can be lost; for example, you can motivate yourself to prepare for an exam by the fear of failure, or by a desire to do well. The former can jolt you into action but the latter is better in sustaining your motivation because it feels good.

Now, there are several categories of positive motivation – it can be useful to become familiar with them as they can help us expand our repertoire of possible ways to motivate ourselves.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

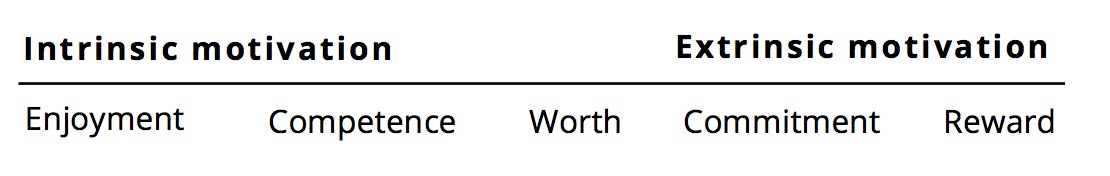

Intrinsic motivation is motivation to engage in an activity for its own sake. Extrinsic motivation is motivation to engage in an activity as a means to an end (e.g. because we are offered a reward, such as money). There is no sharp divide between these types though; they are better imagined as ends of a spectrum:

The following subcategories can be discerned on this spectrum:

- Enjoyment (‘because I like’): you find an activity interesting or enjoyable. A hobby would be a good example.

- Competence (‘because I can’): you perceive an activity as a challenge, an opportunity to test or prove your competencies and powers (e.g. rock climbing).

- Worth (‘because I want’): you perceive an activity as worthwhile doing (e.g. getting physically fit).

- Commitment (‘because I have to / need to’) you have made a promise or have a sense of duty (e.g. meeting a deadline).

- Reward (‘because I will get something out of it’) you engage with an activity because you expect to benefit from it.

Evidence shows that intrinsic motivation fosters creativity(2) and can promote learning and achievement better than extrinsic motivation.(3) An offer of a reward to perform a task that is already seen as enjoyable or interesting can, in fact, reduce intrinsic motivation if it is allowed to take over as a motivator. This is important to be aware of as we still tend to rely excessively on rewards in the workplace, education and personal lives. That doesn’t mean, of course, that these types of motivation cannot be combined when it makes sense (e.g. learning can be intrinsically interesting and enjoyable, but at the same time you can be motivated by your desire to do well at exams). However, intrinsic motivation should be nurtured as a primary motivator whenever possible and we should rely on extrinsic motivation only if the intrinsic one is absent and cannot be incited.

Building motivation

Each of the above categories offer several ways of motivating ourselves and also others:

Enjoyment

- Fun: if an activity is not already fun, link it to something that is (e.g. listen to music or dance while vacuum-cleaning).

- Curiosity, interest, novelty: how can you do what you need to do in a novel way or make it more interesting?

- Company usually makes tasks more enjoyable so, for example, if exercise is a drag for you, find a jogging buddy.

Competence

- Challenge yourself to do something, to do it well, or to do it better than the last time. You can also compete with others.

- Feedback: (self)praise and even criticism that opens up the prospect of improvement can be good motivators.

- Progress or achievement: even a small step that gives you a sense of progress or achievement can motivate you to carry on.

Worthwhileness

- See the value in what you are doing: highly motivated people believe that their actions will make a difference.

- Imagine the outcomes of your actions (e.g. how your room will look when you tidy it up).

- Ideals: linking your action to your ideals (e.g. a belief in justice and fairness) can substantially increase motivation.

Commitment

- Make a promise to somebody – or to yourself.

- Team-work motivates us as we don’t want to let others down.

- Do it out of love (e.g. you may persist with something in order to make your family proud).

Reward

- Treats: promise yourself a treat when you finish a task.

- Enhancing self-esteem: imagine how you will feel about yourself if you accomplish the task.

- Benefits: if your motivation falters, remind yourself of possible benefits (a pay, prize, promotion, recognition, etc.).

Procrastination

Putting off important tasks is one of the biggest obstacles to any achievement, so stop making excuses and deceiving yourself (‘I’ll feel more like doing it tomorrow’, ‘I work best under pressure’). The more you procrastinate, the harder your tasks become. This is because they accumulate or you have less time to do them. Think of it as getting into a cold sea – the more you delay, the more difficult it is to get in, but once you are in you will just swim along! Being lazy and doing nothing can be actually pretty boring and depressing. Achieving something is more fun. Getting started is the hardest part in this respect. So start with small, manageable tasks – one at a time – or say to yourself, ‘I will work on this just for half an hour / ten minutes, and see how it goes.’ Congratulate yourself when you achieve even something small. Priming can help too: focus on wanting rather than on not wanting to do something. Forcing yourself to act may work, but it creates internal conflicts and can be tiring. These exercises can help you enhance your motivation so that you don’t need to force yourself.

Building motivation: take a task that you find difficult to motivate yourself to do (e.g. household chores, revising, exercising, etc.). Go through the above list (e.g. you may try to find something interesting or challenging in that task, you can imagine vividly all the advantages and benefits of accomplishing it, etc) until you come to the point that you actually really want to do it.

Invoking motivation: imagine that you are accomplishing something that makes you feel good; it could be something small and completely unrelated to what you need to do – the point of it is to get into the right frame of mind. Once there, forget about the activity itself and let that feeling of doing something constructive, accomplishment, flood over you. Now approach a task at hand with that frame of mind.

(1) Pintrich, P. R. and Schunk, D. H. (1996) Motivation in Education. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, p.285

(2) Marzano, R. J. et al. (1988) Dimensions of Thinking. Alexandria, VA: ASCD, p.25.

(3) Ibid., p.284.