8. Moods

I try to make my mood uplifting and peaceful, then watch the world around me reflect that mood.

Yaya DaCosta (actress and model)

Moods are states or frames of mind with a global effect on our thoughts, behaviour and feelings. So, although moods can have a specific trigger, they are essentially an unfocused state without an object. Some moods are pleasant (e.g. feeling happy, enthusiastic, powerful, etc.) and some are unpleasant (e.g. feeling depressed, moody, despondent, melancholic etc.). We can’t fully control our moods, but we are not completely powerless in this respect either. Research suggests that ‘individuals who believe that negative moods can be relieved through their own actions are more likely to engage in problem-focused coping strategies and less likely to report depression and somatic complaints.’ (1) So in this area we will consider what we can do in this respect.

Why moods matter

Good moods have a positive effect on mental and physical health, work and relationships. Some unpleasant moods may be useful too. They can make you re-evaluate your situation and initiate change. They can also bring you closer to yourself and help you discover some personal depths. However, some moods can be troublesome especially if they are too intense or last too long. Even pleasant ones can have some negative effects (e.g. they can leave an impression of superficiality or reduce our capacity to connect and empathise with others). Your mood can also affect how you see your situation: we tend to perceive or interpret the situation in such a way as to match our mood (i.e. if you are in a bad mood, you are likely to see your situation in that light) (2). Furthermore, we tend to attract situations that will confirm our mood. So negative moods tend to attract negative situations that, in turn, reinforce our moods – which can become a vicious circle. The longer this goes on, the more energy and persistence is needed to alter it, so let’s see how our moods can be addressed.

The first step: awareness and acceptance

Ignoring or running away from our mood is sometimes tempting but it doesn’t do the trick. Moods affect us even if we do not pay attention to them. It is observed that ‘although our moods may often escape our attention… they can nonetheless subtly insinuate themselves into our lives’.(3) So recognising and acknowledging that we are in a particular mood may be better. This can help us locate the triggers and make some changes accordingly (e.g. if you notice that you are in a bad mood after eating certain food, you may decide to change your diet). This does not mean dwelling on our moods, but making the necessary first step in affecting them.

How to affect intense or prolonged bad moods

- Try first to find the cause of your mood and deal with it. Our moods can be affected by many factors: physiological (e.g. sleep, food, pain); environmental (e.g. crowd, noise, ambience); social (e.g. relationships); and psychological (thoughts, habits, behaviour). Some causes may be complex or deeply buried in the past, so if you can’t do it on your own, ask for help. This exercise may be worth trying too:

Why am I in a mood? Imagine life (it doesn’t matter if it is realistic or not)in which your mood vanished . Now, compare that life with your life as it is. The difference will tell you why you feel the way you feel. For example, if you imagine life in which pets never die, you feel the way you feel because you don’t want to accept the impermanence of life.

- Your mood is influenced to some extent by the way you think. So you can affect your bad mood by recognising beliefs and thoughts that support it (e.g. ‘I wish I was a pop star’, ‘I will never find somebody to love me’, ‘I am good for nothing’). To change them, you can reduce your expectations, and be more accepting/positive of yourself and your situation.

- Finding a sense of meaning and hope can have a profound effect on even long lasting bad moods.

How to affect mild or transient bad moods

- Avoid ‘boom and bust’: chocolate, cigarettes, drugs or alcohol are sometimes used to improve our moods but they create ‘boom and bust’: you feel good for a while at the expense of feeling even worse when their effects wear off.

- Do nothing: just don’t make things worse. You may have noticed that the mind has a natural tendency to moderate our moods: so if you are in a very good mood you may have, in the background, a ‘reality check’ of thoughts or feelings. The same happens when we are in a bad mood. Some ‘silver lining’ thoughts and feelings may spontaneously appear. Things go wrong when these secondary mental processes amplify rather than moderate our moods (bi-polar condition being an extreme case). This is often consciously initiated at the beginning (we want to intensify our immediate state of mind) and then it goes out of control. So the trick here is to resist the temptation to make things even better or even worse and let the mind moderate and balance itself spontaneously.

- Use your imagination: the exercise below is an example of how imagination can be used to change your mood:

Altering moods: close your eyes and relax. Create a mental image that represents your mood (e.g. a cloudy, gloomy day). Then slowly alter the image into one that is

desirable (e.g. a sunny, clear sky). This exercise is more effective if the change is gradual, so don’t rush.

- Entertainment: (a good film, book or music) but it is known that just flicking through TV channels or web-sites can make your mood worse – it has to be something meaningful!

- Do something interesting or something that will give you a sense of progress and achievement (e.g. playing sport or an instrument, writing, studying, making something etc.).

- Socialise: others can be very effective in lifting your mood (although they might have the opposite effect too).

- Help others: this is one of the best mood changers.

How to create a desirable state of mind / good mood

Just getting rid of an unwanted mood may not be enough. Let’s also see how we can actually create a desirable state of mind:

- Our thoughts, feelings, body posture and behaviour all affect out moods. So if you want to be, for example, in a confident state of mind, ask yourself what you would think or do if you were confident, and then start thinking and acting in that way.

- Recall a situation when you were in the state of mind you want to be and allow that feeling to flood over you again. You can do so in your imagination or you can talk or write about it.

- Create the environment that reflects the state of mind you want (e.g. if you want peace of mind clear the clutter in your room or make a habit of going to a park for a walk).

- Many people usually focus on bad things in their lives and take for granted good ones, which, of course, affects their moods. The following exercise can help address this imbalance

The three good things: before going to sleep, think of or write down three good things that have happened that day (e.g. somebody smiled at you, you smiled at somebody, the weather was nice, you felt healthy). Do this for a week (no longer, to avoid making an empty routine out of it).

How to maintain a good mood

- Physical activity, healthy eating and good sleep are essential.

- Prepare for possible challenges. What will you do if somebody or something tries to undermine your state of mind (e.g. you are in a mood to do some work and the phone starts ringing)?

- Moods are often triggered by generalising one experience. For example, your partner upsets you over breakfast and then you project that brief and localised emotion onto other people and situations (friends, work, life in general) and create a lasting bad mood. So, avoiding generalisations is a good way to prevent your mood being spoiled. Think now what can you do or say to yourself if you are at risk of generalising (e.g. ‘I am going to enjoy my day despite this silly argument’).

(1) Salovey, P., Hsee, C. K. and Mayer, J.D. (1993) ‘Emotional Intelligence and the Self-regulation of Affect’ in Wegner, D. and Pennebaker, J. (eds) Handbook of Mental Control. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, p.264.

(2) Frijda, S. (1993) ‘Moods, Emotion Episodes and Emotions’ in Lewis, M and Haviland J. Handbook of Emotions. New York, London: Guilford Press, p. 384.

(3) Morris, W. (1989) Moods, the Frame of Mind. New York: Springer-Verlag, p.2.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

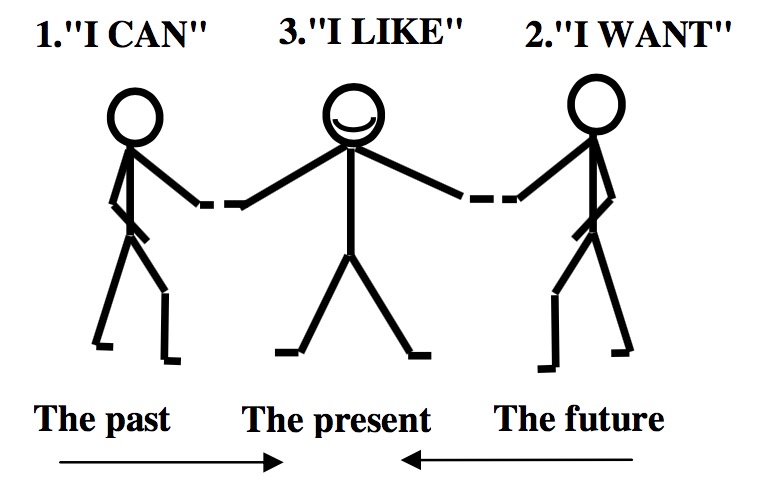

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.