6. Emotional Regulation

Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response.

In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

Attributed to psychologist Viktor Frankl

As indicated in the introduction to this group, emotions are different from feelings. They are not about experiencing but reacting to what we experience, conveyed vocally or through body language and actions (e.g. frowning, crying, laughing, running away, freezing, shouting, fighting). Although these reactions seem involuntary, there is actually much we can do about them.

Managing emotions

Emotional reactions have multiple purposes. They are a way of showing others how we are feeling and can provide us with extra energy and motivation. So, when you need the latter, give yourself a pep-talk or invoke inspirational images – it can make a real difference. However, even enjoyable emotional reactions are not always appropriate (e.g. laughing at a funeral) and can be a hindrance rather than help when facing challenging situations. There are several reasons for that:

- Emotional reactions impair your thinking, assessment and decision-making abilities (try to do maths when emotional, and you will see how much more difficult it is than otherwise).

- They are unlikely to resolve anything, but if they take over, you may do or say something you will regret later.

- They rarely have a desired effect – in fact, they usually make things worse and do not even make you feel better. For example, research suggests that just giving vent to anger does little or nothing to dispel it[i]. In fact, it can become a vicious circle: the more you indulge in it, the more easily it is set off.

For these reasons, it is best to deal with your emotional reactions and the situation separately. This may not always be possible, though, so we will also look at what to do in the heat of the moment as well as afterwards. Finally, we will suggest how to train yourself to respond to triggering situations the way you want.

Dealing with your reactions first

When you notice the welling of emotions, such as anger or upset, remove yourself from the situation and address them first:

- Expend their excess energy on a cooling-off activity – go for a walk or run, have a good cry, or express emotions in writing. Beating a cushion or punch bag is another way to let off steam (but make sure you don’t use others for that purpose). Whatever you do, it is essential to focus on the activity and not let your thoughts and imagination fuel your emotions further.

- When you sufficiently calm down, engage with the underlying feeling that triggered your reaction (e.g. disappointment, hurt, unfairness) and allow yourself to experience it (see Feelings).

- To make sure that your understanding of the situation is fair, accept the facts, but set aside anything you project onto it. Then, consider what would be a wise response.

In the thick of it

If you can’t attend to your emotions first, this is what you can do:

Suppressing or blocking emotions can be useful when you need to be efficient or make an impression (e.g. in an emergency or at a job interview). However, suppression creates an inner conflict that can divert your attention and energy from the situation and may even result in an outburst. It can also lead to completely shutting down, which may be as destructive, particularly for close and important relationships. So, something else is often better:

Defusing your reaction or turning down the emotional valve:

- Notice and acknowledge your reaction (“I am getting angry”)

- Don’t ask yourself if it’s justified (anger always thinks it is); ask if there’s a point, if it helps. If it doesn’t help (anger rarely does), relax and breathe its energy out.

- Try to accept what happened and acknowledge your feelings (you can process them fully later). This should at least soften your reaction, so that it is not uncompromising, righteous, and hard, which is what we usually regret later. Try also to zoom out to put the situation in context, or see its light side.

- Ask yourself what matters most at that point and prioritise that.

In the aftermath

Emotional reactions usually diffuse spontaneously after an event. There are, however, two instances when that does not happen: Emotions remain suppressed: it is well-documented that suppressing emotions has negative consequences for the body and mind[i]. The following exercise can help you release them.

Releasing emotions: if you get tense when thinking about something, some emotions are likely suppressed. Relax your body and mind to let them pass through, but stop thoughts related to these emotions to avoid fuelling them further. If your emotions are very deep or strong, you can express them in writing or art (such as playing music, painting, or drawing). Don’t worry about the quality or content (it doesn’t need to be about the related situation at all) – just let your emotions guide you. Only when you finish, recall the trigger to see if the tension is gone.

The loop is created between thoughts and emotions that feed each other: if not used, emotional energy pushes us to think about the trigger situation: we try to make sense of what happened, justify our reactions, and check if we have done what we could or can still do something about the situation. This initially feels good because it gives us a sense of power. However, this can easily turn into fuelling emotions further. The loop becomes a self-harming, vicious circle that is hard to break out of. This is why thinking and emotions need to be separated. If you have an urge to ruminate about what happened, set aside a specific time for that. If tempted at any other time, remind yourself when you will think about it, before you are caught in the loop (if necessary, jot down a few words to ensure you will not forget your line of thought). If your emotions scream and shout for not being fed, block or defuse them as suggested above. When the time comes, channel that energy into thinking about what can be done and is worth doing. Even concluding that nothing else can be done will give you peace of mind and help you let go and move on.

Choose your responses

Our automatic emotional reactions are not set in stone. If they are unhelpful, we can do the following to respond differently:

- Turn your emotional reaction into another one. Compassion, humour, and love/passion can all be constructive responses. For instance, you can turn an angry exchange with your partner into passion; or if you get panicky in a stadium full of people, focus on cheering your team rather than on how to get out, and you are likely to be fine. Even anger can come in handy (it can get you unstuck if you’re paralysed with fear, for example).

- Replace emotional reactions with better attitudes or mindsets. For instance, you can get serious instead of angry in trying situations. Or, you can act as a professional: don’t take things personally and respond to the situation assertively but calmly. This, though, may need some practice beforehand:

Emotional freedom:

- Consider situations in which you overreact or react inaptly. Don’t focus on what’s wrong, but on finding a right response that will get you where you want to be or achieve what you want in these situations. Let your body and mind experience this response (e.g. if it is calm assertiveness, experience, feel it).

- Close your eyes, relax and imagine a relevant situation. If your habitual reaction starts rising (e.g. you start getting angry), don’t fight it; acknowledge it, relax further, and let its wave pass. You can even act out the anger – do what you usually do – make faces, gesticulate or mime shouting, but without emotions involved. If some deeper feelings arise, attend to them before you move on (see Feelings).

- When your habitual reaction subsides, imagine the situation and respond to it in the way you want. Repeat until the new way of responding comes naturally to you, and then apply it in the real world.

[i] Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional Intelligence. London: Bloomsbury, 1996, p.64.

[ii] See, for example, Pennebaker, J. W. (1988). ‘Confiding Traumatic Experiences and Health’ in Fisher, S. and Reason, J. (eds) Handbook of Life Stress Cognition and Health. New York: John Wiley & Sons, p.670-671.

When we have done what we need to on the inside, the outworking will come about automatically.

Goethe (18/19c German writer and statesman)

This area is not about changing your job, wallpaper, country or partner – it is about changing yourself; in other words, your habitual cognitive, emotional and behavioural patterns.

What do you want to change?

Being able to make a personal change is essential. So this chapter will be very practical and to get the most out of it, it may be a good idea to start by thinking about something that you would like to change. Choose something small because this increases your chances of success and confidence. Define what you want to achieve in simple, clear and positive terms (for example, rather than aiming to lose weight, aim to be fit or to look good).

Prerequisites for successful change

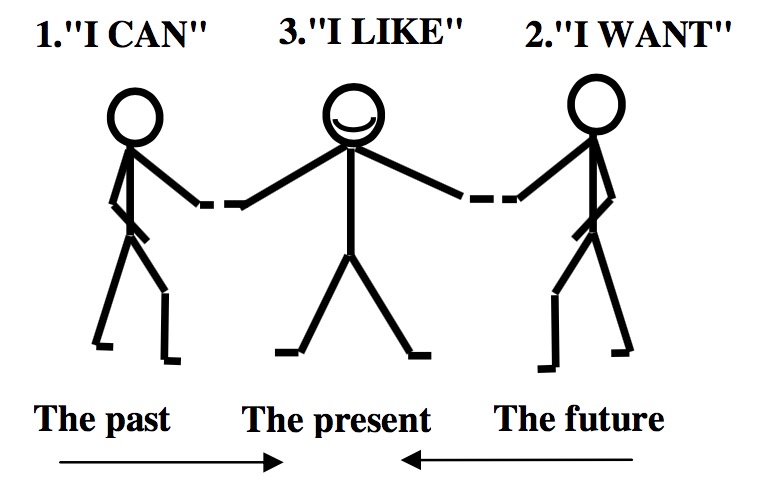

‘I can’, ‘I want’ and ‘I like’ are three conditions for successful change. If all three are present, you can hardly fail!

‘I can’: we are all capable of both failing and succeeding. If you believe that you can’t change, it is true; if you believe that you can, it is also true. To strengthen 'I can', think about successful changes that you have made in the past. If you can’t remember any, just consider that if others can change, you can change too.

‘I want’: you need to believe that the change is worth your time and effort. Filling in this table can help you make it clear:

| Old pattern | New pattern | ||

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

|||

However, if wanting to change is only in your head, it may not be sufficient – the resolution needs to come from your gut. A half- hearted attempt is unlikely to succeed, so make sure that you really want to make a change. The stronger and deeper the feelings associated with the change are, the more profound the change will be. The following interventions can help in this respect.

Wanting change: imagine what your life will look like (in a few days, months or years) if you continue in the same direction. Then imagine vividly that you have changed. What will it look like? How will you feel? Which one is better? Nurture a sense that you can live well without the old habit by seeing life after the change in a positive light.

‘I like’: We can learn to like and dislike something. Nobody likes their first cigarette or first glass of vodka but some persist and learn to like it. If we can learn to like what is not good for us, we can learn to like what is. We can do so by associating a change with a good experience. For example, rather than forcing yourself to eat healthily, find a way to enjoy it: prepare a nice meal and/or add to it something that you already like (e.g. bacon bits, grated cheese, good company, or nice music – be creative!). You can combine this with growing a dislike for the old habit: associate it with unpleasant feelings. 'But', you may ask, 'what can I like if I just want to give up something (e.g. smoking)?' You can like being in charge and free (from the old habit); the benefits of the new (e.g. smelling good, breathing well); the company of likeminded people; yourself, your body, your mind, your life!

The stages of change

It is widely accepted that there are several stages of change(1). Here are some suggestions for each of them:

Learn about your habit

- Its causes: to examine the causes or reasons why you have a particular habit, imagine that you no longer do what you usually do – how do you feel? How can you address the underlying feeling that causes your habit?

- Its triggers: to locate its triggers, observe your habit without any interference. A trigger can be your state of mind, other people or certain events. Consider how they can be neutralised –what else could you do in a trigger situation?

Prepare

- Set an achievable, realistic goal. Bear in mind that a small change is better than a big failure.

- If you have succeeded in making a change in the past, recall what helped you then – the same or similar may help you now.

- Your old habit may be part of a larger picture (e.g. staying out late may be a part of your social life). In this case, you may need to do something about other parts too (e.g. friends who encourage you to stay out late).

- Be prepared for the fact that some people around you may not be supportive: think about who may want (perhaps unconsciously) to sabotage the change and what you can do about it. By the same token, consider who you can talk to or rely on if you are in danger of relapsing.

- Go back to the above table that compares the old pattern and the new one, and consider how you can compensate for the advantages of the former and the disadvantages of the latter.

- Decide if you will make a change gradually or in one go.

- Consider the timing (e.g. if you are taking exams next week, it may be better to make your change after that) and set the date.

- Attempt to make a change only when you feel ready. Are you 100% ready? If you are not, go back to the prerequisites.

Go for it

- Announce your intentions and ask others to support you.

- Stop negotiating with yourself (or you will lose it). Just do it!

- Dis-identify with what needs to be changed and identify with the new (e.g. if you wish to be more outgoing, stop thinking about yourself as a shy person). You can even mentally identify with an image that symbolises the change (e.g. a rock if you want to be more firm with your choices).

Persist

Persistence is essential in this process because old patterns tend to return out of habit. This may be the hardest part (as somebody once said: ‘It's easy to stop smoking, I do it twenty times a day’). However, persevering is worthwhile: in addition to the specific benefits, every successful change also increases your sense of personal power and control. This can help you to persist:

- Use a tempting situation as a reminder to stick to your goal.

- Catch yourself when tempted, acknowledge your feelings and thoughts, and then remember the consequences of backsliding (e.g. how you will feel tomorrow).

- It is much easier to relapse when excited, so be especially vigilant if you notice that you are getting keyed up.

- Use your imagination to put yourself off a temptation (e.g. imagine slime dripping on and covering a cake you fancy).

- Enjoy the new as well as its benefits, and appreciate your achievement (no false modesty, making a change is a big deal!)

If you relapse

If you experience a relapse, accept it as a temporary setback – you are defeated only if you give up! Be aware of what is going on though, as this may help you in the future. Establish why it has happened and develop a strategy for similar situations in the future. For example, if you had a cigarette because you were annoyed, think about what you will do instead the next time you get annoyed. A frequent reason for relapse is forgetting what you have decided. So, remember to remember!

(1) Prochaska, J., Norcross, J. & Diclemente, C. (1994) Changing for Good. New York: Collins.